Jane Sanders took the helm in 2004 after having a successful year as interim president at Goddard College, in rural Plainfield, Vermont, and working in various roles for her husband. In an interview with the Burlington Free Press at the time, she cited building enrollment and expanding the school’s small endowment as priorities. The college adopted a plan to offer more majors and graduate-degree programs, renovate its campus and grow enrollment a couple of years later. And in 2010, Sanders and the board went further: She brokered a deal to buy a new plot of lakefront land with multiple buildings from the Roman Catholic Diocese to replace the college’s cramped quarters in a building that used to house a grocery store. The college used $10 million in bonds and loans to pay for the campus, according to reports by the Burlington Free Press. Maggie Severns, “What happened at Sanders U.,” Politico (Feb. 2016)

Why Burlington College Matters to College Students

Our Modest Proposal noted how the finance industry and its annual fusillade of dour reports against the financial state of higher education may influence executive decision-making regarding fundraising as much as it seeks to influence tuition discounting practices. In a speculative, if tongue-in-cheek piece, we surmised that the annual costs of managing a multi-year fundraising campaign likely exceeds the net benefits of an enlarged endowment, even if the campaign proves successful. We suggested, subtly, that presidents who promote “large endowments” as a future to believe in and who build immense fundraising operations are directing their colleges in a manner far more beneficial to the finance industry than to their own students.

After announcing its pending closure due to the cost of debt incurred based on faulty projections for fundraising and enrollments, Burlington College now stands as the example of how finance industry sophistries about “large endowments” and tuition revenue growth leads to poor presidential decision-making and administrative mismanagement.

According to a report on Burlington College’s financial and accreditation problems in recent years, Dr. Jane Sanders, who served as president from 2004 to 2011, pursued an aggressive strategic plan designed to grow the College’s enrollments, tuition revenue, academic programming, and fundraising. In 2010, Sanders “championed” the acquisition of $10 million in property on which to relocate the campus. Burlington College secured financial backing for the land purchase based on projections that full-time equivalent students and revenue would double in a few year and that the College would raise “‘one to two million dollars per year in capital campaign gifts between FY11 and FY14.'”

As Maggie Severns wrote in Politico magazine, “It’s a formula that has failed colleges and universities across the country.” The formula favored by finance industry credit agencies like Moody’s Investor Services and Standard & Poors: fundraising, tuition revenue growth, and asset acquisition.

While in severe financial and accreditation trouble, due in large part to the debt incurred for the land acquisition, an unrepentant Sanders told Vermont Public Radio:

“We moved from a commuter school to a master’s institution, we moved from one acre to 32 acres and beautiful buildings,” Jane Sanders said. “We had a development plan in place when I left — it was in excellent financial condition. And one only needs to look at the data to see that. The final audit was quite good.”

The data, however, are not so clear.

The Vermont Journalism Trust (VJT) reports that President Sanders overestimated fundraising potential for her five-year campaign by over 600%. In addition, President Sanders may have misrepresented confirmed donations by 300% at the time Burlington College secured the bonds and loans to purchase land for a new campus. Between 2010 and 2014, VJT states that the bank who set the financial terms for credit required the College to secure nearly $2.3 million in “’valid and enforceable commitments of the respective donors and granting parties.’” Sanders signed documents indicating Burlington College had “$2.6 million in confirmed pledges” and projected $5 million total for the fundraising campaign. By 2014, the year its accreditation agency placed Burlington College on probation, the College collected in total only $676,000 in pledges – nearly $2 million short of the “confirmed” figure Sanders claimed four years earlier and over $4 million short of the fundraising campaign.

While the irregularities in the financial data are one facet of the administrative mismanagement that closed the College, the institutional data speak more directly to the administrative priorities of the Sanders administration at Burlington College. The Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System (IPEDS)[1] records a lack of regard for college affordability and student loan debt at Burlington College under President Sanders.

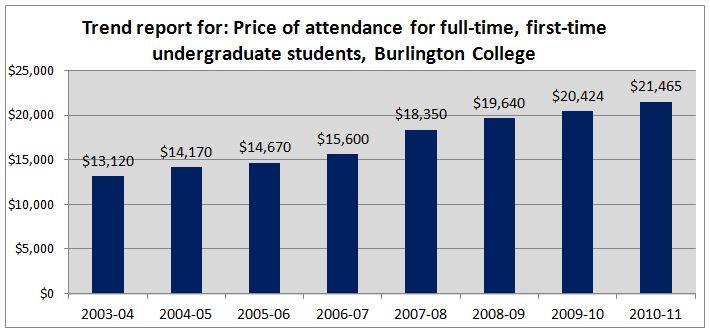

As Figure 1 below illustrates, tuition and fees at Burlington College rose every year under President Sanders. In 2003-04 academic year, published tuition and fees for a full-time freshmen[2] stood at $13,120 per year. At the end of her tenure, tuition and fees had grown 64% to $21,465 per year. During her tenure total full-time equivalent (FTE) students, a standardized measure of student credit activity, fluctuated from 143 in fall 2004 to a low of 125 students in fall 2006 before climbing to 163 in fall 2010. Despite the lack of consistent enrollment growth during her tenure, President Sanders more than doubled tuition and fee revenue from $1.7 million in 2004-5 to $3.9 million in 2010-11, her final year.

Figure 1

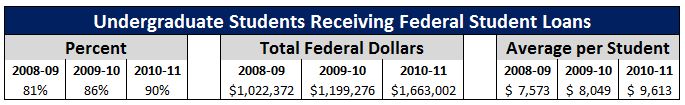

By 2008-09, when most undergraduates would have been recruited during Sanders’s tenure, students were borrowing heavily to pay for a college education at Burlington College. As shown in Figure 2, during the final three years of the Sanders administration, undergraduate borrowing of Federal student loans grew from 81% to 90%, which is to say 9-in-10 students borrowed in order to attend Burlington College. Total tuition and fee revenue derived from Federal student loan aid increased from just over $1 million to $1.66 million in two years. The amount of Federal loan aid per student increased by nearly 27% in these three years from $7,573 to $9,613 on average. In essence, student borrowing drove tuition revenue growth at Burlington College. In 2010-11, at $1.66 million for President Sanders’s final year, tuition and fee revenue from Federal student loans was equivalent to 42% of total tuition and fee revenue for Burlington College.

Figure 2

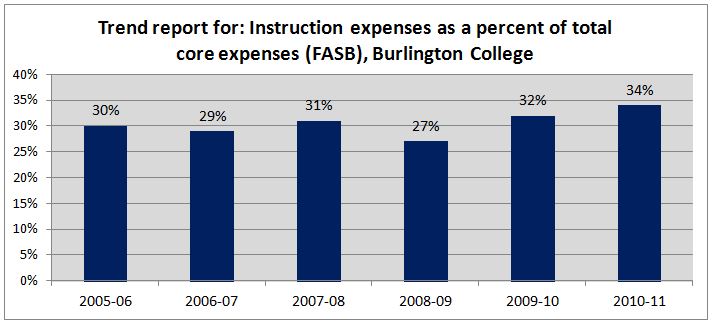

Lastly, as depicted in Figure 3, as the head of a small college, President Sanders did not prioritize expenditures on student instruction. The data available from the final six years of her tenure show that instructional expenses as a percent of core expenses at Burlington College ranged from 27% to 34%. In other words, year after year, Burlington College allocated two-thirds or more of the money collected from student tuition and fees to non-instructional costs — academic support, student services, institutional support, other expenses, etc. Institutional support and other expenses — the administrative expenses most removed from academic instruction and support — consistently consumed around 43% of the college’s budget during her tenure. In sum, President Sanders drove tuition revenue growth largely to fund non-academic activities under her control rather than on academic instruction performed by faculty.

Figure 3

In August 2005, Burlington College reported a six-year graduation rate of 33%. Most of those graduates would have studied prior to Sanders’s presidency or as seniors in her first year as president. In August 2011, Burlington College reported that the Class of 2011, who would have known no president other than Dr. Sanders during their college careers, had the same six-year graduation rate, 33% or one-in-three students. Over the years, the College’s graduation rate ranged from a low of 19% (August 2008) to a high of 45% (August 2010), but no consistent improvement in student success or institutional effectiveness is evident from data reported during the Sanders presidency. Instead, college students at Burlington College found themselves deeper and deeper in debt each year in order to fund tuition revenue growth and, largely, the non-instructional activities of the College.

In other words, Dr. Sanders administered Burlington College in the interest of Wall Street, not students, whether she understood it or not. The finance industry won on both ends: low income students accumulated “huge” amounts in Federal loans in order to pay for capital investment bonds for land acquisitions, fundraising campaigns to enlarge endowments (invested in Wall street equities), and ultimately a presidential severance package.

At the time of her departure, Dr. Sanders “lawyered up” in the words of the VJT, in order to secure a severance package, equivalent to a one-year “sabbatical she earned,” as described by a Bernie Sanders’s spokesperson. In terms of presidential severance packages, $200,000 is unremarkable — if not for Burlington College’s total undergraduate population in fall 2011: 185 students. In effect, students enrolled at Burlington College in fall 2011 paid $1,081 in “other expenses” to compensate a former president for a sabbatical earned from making their college less affordable and no more effective at student success than seven years earlier. One-hundred and fifty-one of those students accepted Federal loan aid averaging $11,009 in order to pay for their college education that year — making former president Jane Sanders’s severance equivalent to 10% of their loans that year.[3]

Approximately 150 current and former college students, most who likely did not graduate from Burlington College, paid for former president Jane Sanders’s severance package in part with Federal student loans and interest — and will do so for years to come.

In large-scale college operations, the figures linking accumulated student debt to cover tuition revenue growth to pay for fundraising campaigns or presidential severance packages will not be nearly as grotesque. Nonetheless, many fundraising campaigns and presidential severance packages — like low-enrolled and highly-selective academic programs — are funded by the students who pay tuition and fees to be instructed at American colleges and universities. Presidents who administer institutions according to priorities like those of Jane Sanders — tuition revenue and endowment growth — are as culpable as faculty for perpetuating structural inequality in higher education. If the campaigns succeed, the financial benefits are directed to honors programs and specialized academic programs that enhance the inequities between programs for “prepared” and “unprepared” college students (Honors of Inequality, Part II). When colleges fail or falter due to the strain of tuition revenue growth on the resources of the nation’s college students or the impossible fundraising goal to build “large endowments” at every college and university, it only plays further into the bleak narrative of higher education in financial crisis peddled by institutions like Moody’s Investor Services.

Burlington College will be remembered for its closure in an era of “higher education in financial crisis,” but the Wall Street formula leading to its failure will be buried under the ideology and vested interests of the finance industry — or, possibly, the ideology and vested interests of “democratic socialism.”

Free College for All!

While our interest lies in understanding how executive decision-making geared toward tuition revenue growth and fundraising campaigns perpetuates structural inequities in student debt accumulation and outcomes, the foregoing analysis lends itself to a few words on “free college for all” as proposed by the Bernie Sanders presidential campaign. The Sanders campaign has not offered any substantive comment on the failure of Burlington College. So, others must speculate on the links between President Jane Sanders’s administration of Burlington College, its significance to democratic socialism for higher education, and the fervor of “free college” populists.[4]

The College for All Act clearly reflects the program of a politician from a non-diverse state — or a former college president wed to a U.S. presidential candidate — who understands college opportunity as a question of tuition revenue, endowment, and enrollment growth rather than in terms of institutional and educational effectiveness.

Free college for all — no less than the unicorns of data science and the cant of academic preparedness & engagement — will serve to perpetuate the structural barriers to higher education for non-traditional and disadvantaged students and will further widen social inequalities between college graduates and non-graduates. An open spigot of per-student federal funds distributed to the nation’s colleges will provide a monstrous flow of revenue to state public colleges subject to nominal rules on expenditure and no apparent accountability for performance. Those colleges will collect federal and state funds for accepting low income and underrepresented students, but then face no prohibition on redirecting those funds to pay for honors and other costly specialized programs of instruction for “prepared” or “non-marginal” students who most interest faculty, administrators, and board members. The journey of nontraditional students will continue to be “segregated” and the experience of low income students will continue to be daunting if federal funds are not required to support the specific students targeted by the federal funds. In other words, “free college for all” will benefit traditional college students over non-traditional students, as the Brookings Institute finds.

In addition, free college for all at public schools does little to alleviate the crushing debt of American students who study in our nation’s private, non-profit colleges and universities. Students such as those served by Jane Sanders at Burlington College or at private, non-profit HBCUs remain largely neglected by the College for All Act and Bernie Sanders’s presidential campaign. While the Act proposes measures to use federal funds on states’ “higher education systems, on academic instruction, and on need-based financial aid,” the proposed Act does not specify that the federal funds received should be used directly to educate the low income and underrepresented students who are most in need of those funds — and who bring those awards to their college of choice. Further, research shows that underrepresented students – low income, minority, and first-generation college students – require substantive student service and administrative support. Thus, the prohibition on expenditures for “administrator salaries” will by necessity direct federal funds to the private sector in order to provide high-end “higher education systems” (e.g., data science) and student services (e.g., learning analytics) to college students. In other words, “free college” will benefit traditional, affluent, and “prepared” college students at the expense of non-traditional, low income, and “unprepared” college students, while forcing public colleges to outsource student success initiatives aimed at underrepresented students to questionable education technology entrepreneurs in the private sector.

In the final analysis, The College for All Act or “free college for all,” despite its allure to certain demographics of college-aged voters, is nothing more than a revenue boon for public colleges’ honors programs and low-enrolled selective programs disproportionately serving traditional students, while also creating a prohibition on administrators’ salaries that inadvertently forces public colleges to outsource to the private sector their administrative responsibilities for the student success of underrepresented and nontraditional students.

As such, the proposed College for All Act is democratic socialism for children of the affluent, the ed-tech hucksters, and venture capitalists.

- IPEDS data may contain inaccuracies. We do not consider the potential for inaccuracies in any of the Burlington College figures cited or the possibility of data misreporting by the Sanders presidency.↵

- IPEDS variable “Trend report for: Price of attendance for full-time, first-time undergraduate students (academic year programs), Published in-state tuition and fees 2014-15”↵

- Of course, one might say those funds came from another fund, but allocations between funds eventually shift the cost of operations to current or future students. As an allocation in core operations for students, a severance package for a former president must rank low as a benefit to current and future college students.↵

- Articles reviewed to construct an analysis of Burlington College inadvertently led to articles on the Sanders campaign, including those by The Atlantic, The Washington Post, The Vermont Journalism Trust, Politico, Vanity Fair, VPR Vermont’s NPR, Burlington Free Press, and others linked to in the text.↵