Introduction

In one respect, institutional researchers have begun the process of reorganization to reshape the profession in a fashion that is more consistent with its roots in the practices of social science. The Association for Higher Education Effectiveness (AHEE) advocates for an integrated institutional effectiveness office that encompasses areas that include the portfolio of research developed in the 1950s and 1960s.[1] Nonetheless, the portfolio of research or integration of institutional research functions under a single institutional effectiveness office is not a sufficient condition to advance the practice of institutional research as a social science and the effectiveness of higher education institutions. As E. Bernadette McKinney and John J. Hindera wrote in 1992, with resignation to the dominant paradigm:

If institutional research were not so dependent on the perceptions of those within a particular institutional context, it might be possible for a discipline to emerge… For the most part, others set the agenda for institutional research… There is little incentive for this [to] change.[2]

The disciplinary paradigm rooted in institutional particularity has limited the types of questions and the priorities of the institutional research agenda for higher education. Resignation to this paradigm has damaged most significantly the concerted development of institutional research instruments and methodologies to foster the accumulation of knowledge about higher education settings.

Accordingly, this search for a new paradigm for institutional research as social science is not intended to be conclusive so much as evocative – of past visions, present impediments, and future possibilities. The potential to re-structure institutional research as scientific inquiry requires a standard technological infrastructure to facilitate collaboration, experimentation and replication, and discourse across multiple institutions without regard for the institutional type of the administrative researcher. In the first part of our search, we have defined five principles for a new paradigm for research on higher education that recognizes the origins of modern scholarship on higher education in institutional research and embraces the profession of institutional research as a scientific discipline. In part II of the search for a paradigm, then, we consider the practical prerequisites for the practice of institutional research in scientific investigation: the institutional research apparatus.

The Problem of Technology and the Discipline of Institutional Research

In his work on the structure of science and scientific revolutions, Thomas Kuhn notes there are “only three normal foci of factual scientific investigation,” which may be characterized: 1) facts of the paradigm refined by measurement and scope, 2) facts predicted by the paradigm and tested by measurements, and 3) facts derived from ambiguities and unresolved problems of the paradigm. In reference to the first, Kuhn observes, “Again and again complex special apparatus has been designed for such purposes [refinement], and the invention, construction, and deployment of that apparatus have demanded first-rate talent, much time, and considerable financial backing.”[3] Aside from a few branded instruments relying on a twentieth century research methodology in decline – student benchmark surveys – it is difficult to point to any integration of methodology and technology that amounts to a “complex special” institutional research apparatus. For twenty or more years now, institutional researchers have received messages about the threat of technology to their practices from leading scholars of higher education and at their association forums – messages that run contrary to Kuhn’s observation. Consequently, a casual mental review of the technology of institutional research soon reveals that there is no authentic institutional research apparatus.

In the absence of leadership from scholars for the development of technology to advance institutional research as a mode of scientific research in higher education, technology companies have offered a growing catalog of software that is too numerous and too frequently launched in Silicon Valley to be counted accurately: data warehousing, visualization, document management, student success solutions, etc., etc., etc. Yet, none of these products, with perhaps the exception of assessment software, are designed to facilitate institutional research as a disciplinary practice. Computing technology comes to institutional research without direct insight into its practice – and this has been the case since the beginning of the profession.

At the fourth meeting (1964) of the National Institutional Research Forum,[4] the predecessor of the Association for Institutional Research, the sessions on the final day considered new technologies for institutional research and reflected, in part, the path of computing and automation in higher education. G. Truman Hunter, of IBM, presented on the company’s University and College Information System (UCIS): “a framework which each institution can modify to create a management control system which will help those in charge solve today’s problems and plan for tomorrow’s needs” (59). Vernon L. Hendrix, of UCLA, then followed with a paper on “administrative” (operations) research: “the systems approach… [that] seeks to find the best decision for the total institution or operation” (67). “Management control” and “decisions” are featured as the ends of institutional research. With the IBM solution, institutional research may engage in “a variety of studies… to construct and solve models which represented relationships among factors and objectives [inputs and outputs]” (74). In these two presentations, the information technology solution for institutional research as data processing and decision support is clearly evident.

While the first two commentators expressed skepticism for the technological proposals of IBM and its operations research agenda at the forum, Keith W. Smith of Southern Illinois University presciently counseled his colleagues, “I think the advent to total information banks, and the accessibility to them, are certainly a near reality. They are going to be in our institutions very shortly, for better or for worse” (91). For better, as Smith notes, “the application of operations research techniques to decision-making and planning in higher education” may lead to better judgments “with data available immediately…” For worse, evident in the words of Hunter and Hendrix above, the technology company representatives’ understanding of a research system encompassed only the “total” operation of a single institution and its decision-makers. Accordingly, in the intervening fifty years, the implementations of computing technology such as student information systems and ERPs have serviced the particularities of higher education institutions. Colleges and universities adopted solutions largely requiring the oversight and skills of technology professionals accustomed to working in terms consonant with institutional particularity. Subsequently, institutional research in general became dependent on technology companies’ solutions and, today, institutional researchers begin within a pre-defined range of functionality and flexibility to support their research as determined by the product road-map of the companies who won contracts with the institutions.

Three complications for the practice of institutional research ensue from the dependency on technology companies. First, the companies leading the design of critical solutions for the practice of institutional research have little-to-no experience with research and study of higher education. Second, technology solutions provided by these companies service the transaction procedures and “requests” of disparate functional units without regard for a standardized system of information storage. Third, the tertiary systems like data warehouses, often regarded as feature services for institutional research, extend the particularity of the local institutional systems, resulting in the proliferation of disparate and non-standardized research data sets that lack correspondence between institutions. Thus, the methods and technologies for the simplest tasks in institutional research – data extraction and definitions – differ widely by institution and the most basic aspects of institutional research – external reporting – require the support of data analysts in the institution’s information technology departments. To the degree that the technology is incapable of supporting institutional research, needless acrimony between information technology and institutional research offices surfaces. It is little wonder that officers of institutional research and effectiveness offices easily become overwhelmed by the “burden” of institutional reporting in such conditions.

While the larger and wealthier institutions in the United States may spend millions on companies that provide data warehousing and visualization solutions, the implementations again follow no standard architecture and, ultimately, reinforce the misguided notion that local particularities of colleges and universities determine what passes as fact in institutional research. Certainly, a number of such institutions across the country have the staff and budget to pursue portfolios of institutional research that suit all nine modalities of the original research offices of the 1940s to early 1960s. Whatever the portfolio of institutional research, however, applied research using data warehouses, each with their own data architecture and specifications designed to service the “perceptions of those within a particular institutional context,” cements institutional particularity into the apparatuses of institutional research. The inability of institutional researchers to replicate studies and generalize findings in higher education in general then precludes the formation of a substantive discourse to scrutinize each others’ results and to accumulate knowledge as a discipline.

Ultimately, computing technology is an inefficient and ineffective substitute for a social science. In practice, technology company’s solution to facilitate “data studies” by virtual offices and ad-hoc committees can satisfy only the three simplest principles for scientific research in education: pose significant questions, direct investigations, and chains of reasoning. Scholars of higher education, those wed to the Michigan State paradigm that advocates for virtual offices in particular, may be quite happy to end their reflections on institutional research as social science at this point. Most, however, then fail to recognize that the failure of scholars to lead in the development of technology to advance institutional research stems directly from their presumptuousness about the differences between institutional research and scholarship on higher education. Such scholars, also, blithely ignore the works of institutional researchers who established the profession and offered a vision for institutional research technology that serviced the three principles of scientific research that from the basis for a scientific community of scholars: links to theory, replication and generalization, and professional discourse and scrutiny.

The Applied-Basic Method of an Apparatus for Institutional Research

Institutional research entails praxis, even if unstated or understated, that implicitly links to “some overarching theory or conceptual framework” to structure inquiry. In addition, in its praxis, institutional research embodies replication and generalizability across studies as the fundamental goal of its investigations, reproducing measurements “in a range of times and places” to contribute to the integrated and synthesized findings of scholarship. And, thirdly, institutional research, under the guise of “external submissions,” at its most basic level of praxis, “discloses research… to scrutiny and critique,” to provide an ever-growing body of measurements and knowledge that may foster a “professional community of scientists.”[5] These qualities are found in any number of resources for institutional research, including the survey materials for IPEDS submissions, the many methodological contributions of authors in the series, New Directions for Institutional Research or AIR Professional Files, and now, with more frequency, grants to institutions for the study of higher education to inform decision- and policy-making such as research to support the What Works Clearinghouse. From reporting to planning to effectiveness studies, that is, institutional research follows tendencies toward the generalization and accumulation of knowledge as a social science.

With respect to external reporting, while many practitioners often lament “the burden,” the advancement of institutional research as a social science is recorded in the statistical records of the federal government and the National Center of Education Statistics. In 1967, R. J. Henle published a 444-page report on an NSF and NIH sponsored research project that engaged eight universities for the development of “systems for measuring and reporting the resources and activities of colleges and universities.” In the forward, Henle states, “[T]he final goal envisioned and described the Project – the concept of a total information system which would be broadly compatible between institutions – is, to some extent, being brought closer to reality…” In the development of a “total information system, the Project directors were mindful of the need to link research to theory” and proposed an “analytic and philosophical view of higher education” to inform a comprehensive system in which “the information systems of all levels of education must be capable of being intermeshed… [to] fit into the totality of the scientific community.”[6] The report considered systems to measure student, faculty, personnel, facilities, and financial data and provided detailed recommendations for the elements in a total information system for higher education. In an era before sophisticated student information systems, the report exemplifies an approach to institutional research for external reporting as a social scientific endeavor and makes explicit the need to overcome “the lack of correspondence among the measuring and recording procedures and the cataloging of data by different agencies” (4).

Henle’s comprehensive system never came to fruition. Nevertheless, the Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System (IPEDS), implemented between 1985 and 1989, represents a partial fulfillment of the vision for between-institution investigations proposed by Henle and his project contributors.[7] With the exception of facilities, IPEDS components record institutional characteristics, student data, personnel, and financial data for colleges and universities “at all levels.” While its not an exhaustive catalog, the components and survey items developed over the past 30 years designate a “class of facts” for institutional research to investigate the “nature” of higher education settings. Though not ideal for independent scientific research, the Technical Review Panel process provides some assurance that IPEDS components and survey items, in definition, measure what they purport to measure with a degree of validity. What the IPEDS components and survey items provide, then, are standards for the measurement and reporting of resources and activities by colleges and universities for a class of facts suitable, largely, for annual measurement and investigations.

In annual reporting process, the praxis of institutional research in the pursuit of reliability ingrains the research parameters and definitions of IPEDS across multiple institutions.[8] When a request for a variable, for instance enrollment headcount, comes to an institutional research and effectiveness officer, consider what has been done in preparation to respond to the request with reliability and validity, having prepared variables for IPEDS submissions:

- Variable definition: IPEDS provides a general definition of an enrollment derived from prior institutional research standards and/or recommendations from a panel of researchers that serve as the structure of systematic inquiry.

- Variable application: At the institutional level, the institutional effectiveness officer applies the general definition to institutional business policies and procedures for enrolling students to understand how the particular aligns with the general.

- Variable specification: Student information systems form electronic repositories or archives of the institutional business practices and decisions – the individual transactions reflecting the operation of business policies and procedures – thus, in part, standardizing data fields by virtue of the architecture, functionality, and local configurations to measure normalized events (enrollments, payments, grades, etc.).

- Variable syntax: Using research software such as SPSS, SAS, R, etc., the institutional effectiveness officer imports records from the information system and then recodes, computes, aggregates, etc., until the work results in a variable with values aligning the local application and specifications to the general definition.

As an institutional effectiveness officer has taken steps to create a variable, s/he has also taken equally rigorous steps in defining, applying, specifying, and writing syntax to create a unit of analysis (enrollment on such-and-such date) that is appropriate for an enrollment headcount. In the end, what the institutional effectiveness officer has created is rightly regarded as a “data set” – not data. Set-making is the combination of variables and units of analysis for a specific research design and purpose. And, then, when the researcher generates frequencies, counts, means, significant differences, etc., from the data sets, s/he is statistically analyzing the relationships defined in the data set between the variables and the unit of analysis or between variables juxtaposed by a unit of analysis. All of these steps and more represent an exhaustive research methodology to answer a fairly simple question: what is the enrollment headcount? The statistical analyses of institutional research entail rigor and expertise in nearly every submission whether the practitioner recognizes it or not – certainly for every request answerable by data sets produced from IPEDS specifications. Thus, while institutional researchers indirectly set standards, the praxis of institutional research runs counter to the particularizing momentum of information technology solutions, requiring – and introducing – theoretical knowledge in the form of general standards, definitions, and systems into the measurement of activities at colleges and universities as a whole.

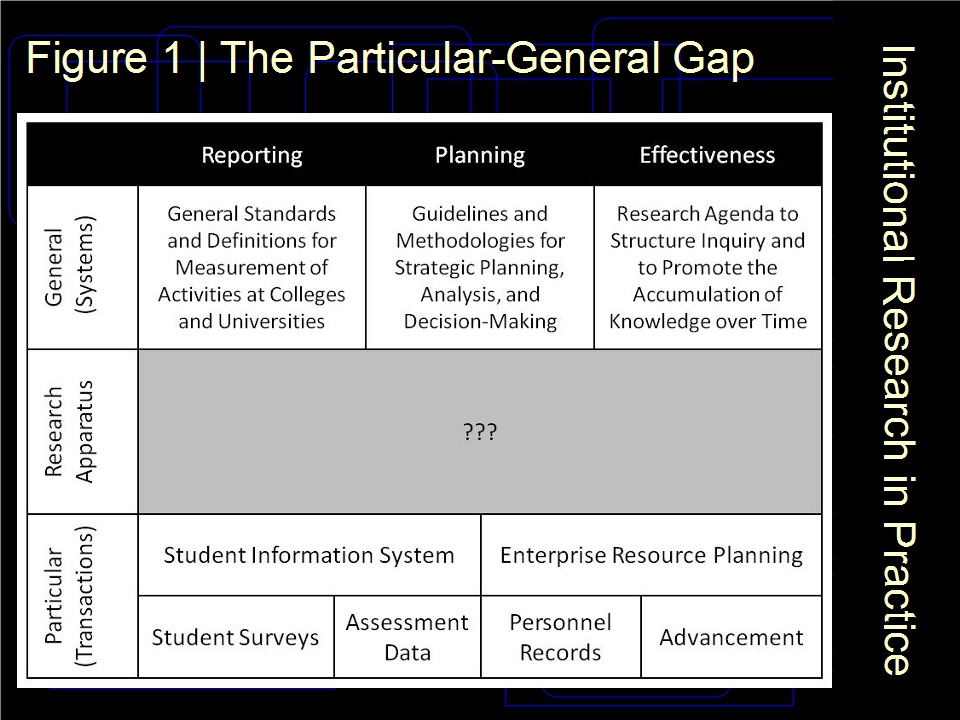

Henle’s ideals of a total information system is rooted to a vision for a scientific community of institutional researchers. Whether in the performance of external submissions, decision-support systems, or social research, as represented in the general row in Figure 1 above, the institutional research apparatus is the layer that translates concrete transactions at a particular institution into the data representing abstract concepts for study by a scientific discipline – it is the layer in which the “three normal foci of factual scientific investigation” (Kuhn) may take place. The barrier, then, for institutional research as a social science rests almost entirely in restrictions placed on replication by the current approach to building the institutional research apparatus for colleges and universities. First, to be clear, replication is not a hollow ideal that represents what may be done with scientific research; replication is a requisite practice for a healthy scientific community.[9] Scientific research in higher education calls for theory and practice to be tested and re-tested to reveal the variability of results, the reliability of analysis, and the validity of paradigms. For this to occur, however, institutional research requires machine processing, or automation, on a scale and in a manner consonant with social scientific practices. Although the Michigan State School of Institutional Research and apprehension for technology expressed by scholars of higher education derailed its progressive development, early practitioners once again provide a platform from which to re-envision an institutional research apparatus that will advance social scientific investigations at any institution.

In one of the first substantive publications on institutional research, Edward M. Stout and Irma Halfter of DePaul University contributed an article to the collection edited by L.J Lins, “Institutional Research and Automation,” that outlines the characteristics of an apparatus for institutional research.[10] In an era that predates the reversals of Dressel and his many followers, Stout and Halfter did not presume a difference between institutional research and research on higher education. While their piece does not anticipate the technological transformation in “automation” and machine processing that has taken place in the past 50 years, their guidance for the organization of institutional research as scientific investigation provides insights that are generally lost in the subsequent scholarship on higher education. In perhaps their most notable difference from the Michigan State School of Institutional Research, Stout and Halfter regarded institutional research’s “contribution to theoretical knowledge… [as] the ‘main-line’ investigation, with practical considerations being second” (96). Thus, research at one particular institution was not a categorical bar to theoretical work:

To merit the title “research,” institutional research, just as scientific investigation in the natural or social sciences, implies not only empirical evidence and method but also the primary of objective of true research: a contribution to theoretical knowledge. This is so even though the inquiry be pursued on a single institutional level. The investigation should produce a design that can be replicated and which can, therefore, be broadened to an inter-institutional inquiry (95).

Stout and Halfter distinguish institutional research qua social science from “action” research [quotes in the original] and evaluation: “The statistical inquiry of institutional research, as is characteristic of any scientific investigation, should be expected to yield a search for principles with some degree of generality even at the single institutional level” (95). In a series of guidelines for automation for institutional research, the two also maintained a distinction between the viewpoint of data processing for student information systems and the viewpoint of data processing for “the art of research design,” noting: “researchers insist on flexibility… The [research] problem and the steps necessary for its elaboration must have priority over machine solutions” (96). Their efforts to organize research along these lines “on a three year time table” yielded multiple benefits over time, including “refinement of hypotheses,” “new lines of inquiry,” and “a body of data” [i.e., class of facts] that was suitable for comparative analysis (97).

The design principles of Stout and Halfter, if combined with the general standards for between-institution research (IPEDS), provide a platform from which to launch scientific investigations within-institution research. When followed as specifications for the design and implementation of a total information system as envisioned by Henle and early institutional researchers, the IPEDS component and item specifications produce several comprehensive and multipurpose data sets for the study of college and university activities at the sub-institutional record level (student, enrollment, employee, department, etc.): degree completions, 12-month enrollment, fall enrollment (including student financial aid variables), first-time freshman cohort (including graduation rate variables), admissions, human resources, academic libraries, and finances. When built to specification and longitudinally, the IPEDS-derived record-level data sets are broadly compatible across multiple institutions and set the foundation for collaboration by a community of scholars working with a common “class of facts” to investigate the nature of higher education settings. Further, to advance strategic planning, these data sets may be combined in various ways to serve a typical portfolio of strategic research. The 12-month enrollment data set (enrollments) merged with the human resources (personnel records) and finance (departments) data sets yields a rich resource for Academic Program Review. Admissions and fall enrollment data sets combine to form the basis for strategic enrollment management and retention models. And so on, and so on.

Considered in conjunction with Philip Tyrrell’s theoretical basis for institutional research and Henle’s architecture for a “total information system” of measuring college activities, Stout and Halfter supply the outlines of an institutional research apparatus that leverages technology designed for the advancement of scientific investigations concurrently between and within institutions – the applied-basic method of institutional research. In sum, the praxis of institutional research revealed to these thoughtful scholars, as recorded in their works, what is necessary for the design of computing technology that provides the most value to colleges and universities and the apparatus for institutional research as a social science.

(In)Conclusion

James Doi noted at the 4th meeting of the National Institutional Research Forum in 1964:

Not infrequently an institution will appoint as IR director an individual with competency in certain kinds of studies that are of immediate interest to it–for example, budget analysis and cost studies, or enrollment projections and student characteristics, or curriculum analysis and educational experimentation. Within a two- or three-year period, studies of a given type should become a matter of routine and the institution reasonably well informed of the situations that encompass them. Other problems in other areas requiring analysis may then come to the forefront. The director of IR should be able to provide the knowledge and leadership in the study of such other problems, if not, the administration will have no other recourse but to regard the office of IR as a repository of more or less routine, perhaps even unimportant, studies… As a minimum…. [the IR director] should acquire knowledge of the kinds of studies developed by others engaged in research on higher education and of the their relevance and applicability to the problems faced by his institution…

As evidenced by the research of the National Association of System Heads (NASH), Doi’s warning to a single institutional research office applies more generally to the malfunction of institutional research as a profession and scientific discipline today. And, although Doi had a single institutional research office in mind, his recommendation for knowledge and leadership in the study of higher education applies equally to the profession of institutional research and its potential as a discipline.

In this two part brief, we wished to recover the thoughts of early practitioners who – with an intellectual freedom and honesty to consider the possibilities of institutional research at its origins – recognized the need for an authentic institutional research apparatus to empower a scientific community for the study of higher education settings. In many respects, these institutional researchers were far ahead of their time in their consideration for the needs of their profession before the widespread existence of key technologies: student information systems, statistical software for the social sciences (SPSS), spreadsheets, visualization software, intranets, color monitors, etc., etc. In a manner, this group of peers exemplified the best principles of a scientific community when they began the process of generalizing standards and definitions, imagined technological apparatus to enable replication, and engaged in promising discourses on the research agenda of institutional research.

While their vision may not have come to fruition in the ensuing years, their framework of a paradigm for institutional research as a social science remains – and is more so within reach today.

- See the white paper by William E. Knight, Developing the Integrated Institutional Effectiveness Office posted on the AHEE Web site at http://ahee.providence.edu/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/Developing_the_Integrated_Institutional_Effectiveness_Office_Knight_W_April_2015.pdf.↵

- E. Bernadette McKinney and John J. Hindera, “Science and Institutional Research: The Links,” Research in Higher Education Vol. 33, No. 1 (Feb. 1992), 28. Neither McKinney (law, medical) nor Hindera (political science, law) appear to be scholars of higher education and their publication on science and institutional research in the the AIR’s flagship journal, Research in Higher Education, carries no particular authority. I cite their article merely to bring attention to their use of institutional particularity and their peculiar resignation to the status quo, the Michigan State School of Institutional Research, in an article published by the editors of the leading institutional research journal. The abstract asserts that “institutional research… is distinct from science…” – a statement that is, prima facie, of the highest quality and of interest to scholars of higher education.↵

- Thomas S. Kuhn, The Structure of Scientific Revolutions, Second Edition, Enlarged (Chicago: 1970), 25-27, 25 (quote).↵

- Clarence H Bagley, ed., A Conceptual Framework for Institutional Research, The Proceedings of the 4th Annual National Institutional Research Forum, (Pullman: 1964).↵

- Quoted lines from the six principles of the NRC in Scientific Research in Education, pages 3 to 5.↵

- R.J. Henle, Systems for Measuring and Reporting the Resources and Activities of Colleges and Universities, (National Science Foundation, Washington, DC: July 1967), vii, 3.↵

- Notably, both Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute (Philip Tyrrell) and Michigan State University (Paul Dressel) participated in the NSF sponsored project.↵

- The following thoughts were first posted in another version in a forum of the New England Association for Institutional Research.↵

- As recently affirmed in reports on the inability of scientists to replicate Psychology research studies. The problem is certainly more severe in education research, according to Matthew C Makel and Jonation A. Plucker, “Facts Are More Important Than Novelty: Replication in the Education Sciences,” Educational Researcher Vol. XX No. X (2015), 1-13.↵

- We have used the Lins volume in prior briefs to call attention to the vision of Philip Tyrrell and the portfolio of institutional research represented in the 1962 collection. Stuiart and Halfter’s article follows Tyrrell’s, in L.J. Lins, ed., Basis for Decision: A composite of Current Institutional Research Methods and Reports for Colleges and Universities, released under The Journal of Experimental Education Vol. 31, No. 2 (Dec. 1962), 95-98.↵