A Practical Discovery about Tuition Discount Rates

Among the many bytes of data driving decision making in institutions of higher education, the tuition discount rate, or “tuition discounting,” invites some of the most voluminous and discomfiting commentary in the public space. As the Google Ngram Chart below shows, tuition discounting registered the attention of education and policy authors beginning in the late 1980s and early 1990s, then steadily mounted until the mid-2000 decade. One of the first publications from this era, by the National Association of College and University Business Officers (NACUBO), notes that tuition discounting should not “be feared or abandoned.” The benefits of tuition discounting can be measured in the promotion of educational access, student diversity, and “increases in the marginal revenue of the institution.” The author cautioned that revenue maximization failed to justify tuition discounting if “the price of education rises above the payment capability of increasing portions of the population,” but did so in the context of providing a model to understand and monitor tuition discounting to improve the management of higher education institutions.[1] In later years, NACUBO has sponsored its Tuition Discounting Survey to track the college and university trends in tuition discounting. The association continues to provide measured analysis of the tuition discounting practices by private, nonprofit four-year colleges and universities. In its most recent public release, the association notes that enrollment factors pressured institutions to become “more strategic with their aid packages,” but that “80.4% of [institutional] grant dollars… met students’ financial need in 2012-13.”

Figure 1 | Google Ngram for Incidence of “Tuition Discounting” from 1980 to 2008

On the other hand, financial institutions have increased scrutiny for tuition discounting by colleges and universities and sounded an alarm for the sustainability of the private, nonprofit sector in higher education. Moody’s Investor Service fuels the annual news cycle with its releases about what it characterizes as a distressed higher education market.[2] “Weakened pricing power and difficulty in growing enrollment are impeding revenue growth,” Moody’s announced in early 2013. “Net tuition revenue growth [revenue from tuition after discounts] for US nonprofit colleges and universities in fiscal 2015 will be the weakest in a decade,” according to its November 2014 release. In the release, Moody’s notes, “We project private universities will have 2.7% net tuition revenue growth…. ‘despite overall stable enrollment.'” News agency for the higher education sector then broadcast the prognostications to a larger audience. “Economic and demographic shifts are undermining the ability of all but the most prominent colleges and universities to profit off high tuition prices,” begins an article in Insider Higer Ed, covering a recent release by Moody’s. The Hechinger Report asserts, citing the analysis and projections of the November 2014 release by Moody’s Investor Service, that many institutions “will see their revenues fall behind the 2 percent inflation rate…. because private universities are being forced to give higher and higher discounts to keep students coming.” Positioning revenue growth and tuition discounting as antagonistic elements, purveyors of financial outlooks for the private, nonprofit sector of higher education imagine a pall hanging over most institutions.

In putting the question of tuition discounting in these terms, the dour public discourse on tuition discount rates and revenue forecasts for private, nonprofit institutions from the financial and news industries produce very real and potentially detrimental outcomes on decision-making at private, nonprofit colleges and universities at the institutional level. I recently consulted a private, nonprofit 4-year institution regarding the strategic tuition discount rate for its college. I learned that the internal dialog at the college revealed a reluctance to consider any tuition discount rate in excess of 49% for its first-time, full-time freshman class. Moody’s Investor Service had recently released an announcement in which it called out an increase, from 5% in 2004 to 12% in 2014, in the proportion of institutions that offered tuition discounts over 50% to first-time full-time freshmen. Whether from direct input from a Moody’s representative or the tenor of the reporting for tuition discounting by higher education news outlets, this institution previously had set for itself an upper bound limit of 49% for its tuition discount to incoming freshmen. Trend analysis from the college’s institutional research and planning office, however, suggested that the local market competition in an “overall stable enrollment” environment (to use Moody’s words) required that the college consider no less than 50% as its tuition discount rate for admitted first-time students. For the president, the decision to discount below or above 50% presented immense difficulties either way – risk being flagged by the financial or news industry as a “tuition-dependent” institution on the edge of collapse because it was “forced” to provide a discount rate above 50% or risk offering an insufficient discount rate that failed to yield the targeted number of new freshman to sustain the normal operations and planned growth of the college.

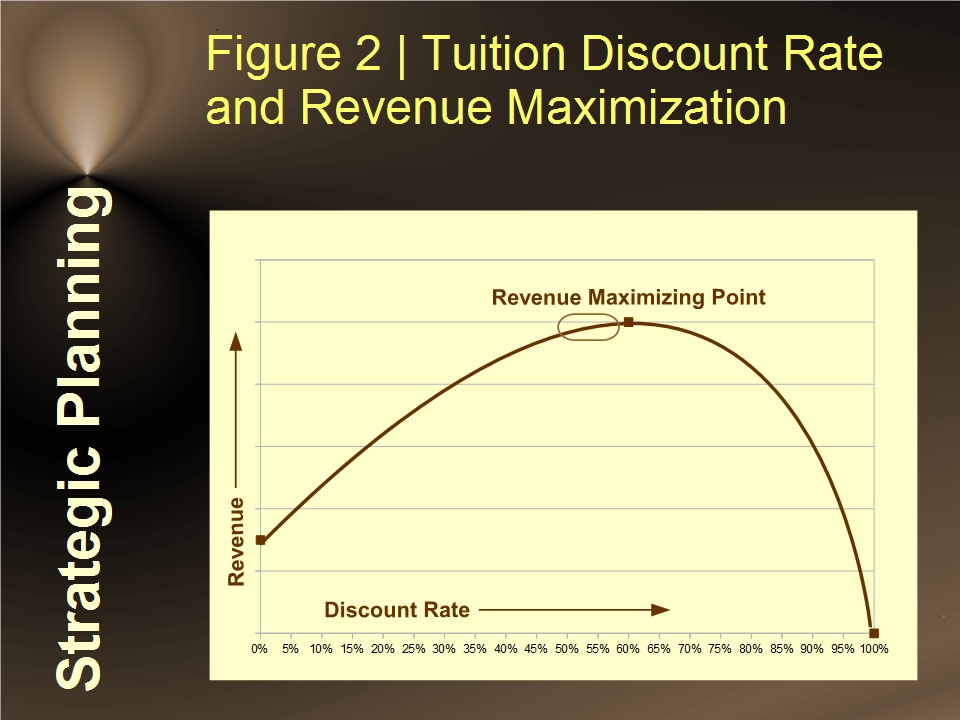

Fortunately, through a different vendor, the college had a predictive enrollment model for tuition discounting based on a theory similar to the Laffer curve in taxation, as illustrated in Figure 2. The tuition discount rate, as suggested in the model from NACUBO over 20 years ago, will increase the net tuition revenue of a college to a point, but then results in a loss of tuition revenue when the cost of discounting for all enrollments exceeds the revenue from one additional enrollment – the point of revenue maximization as seen in the graph. In private discussion with the president, we both realized that the college had not received from its vendor the exact tuition discount rate that maximized its tuition revenue and we initiated the analysis through his enrollment management office.[3] What we learned was that the college’s discount rate to maximize revenue from entering freshman was well beyond the arbitrary and normative figure of the 50% discount rate favored by financial and news industry experts. Applying our findings, the college was able to consider a wider spectrum of scenarios for discount rates, enrollment headcounts, and tuition revenue than it otherwise would have considered if the 49% limit on the tuition discount rate had prevailed. As a result of the perspicacity and leadership of the president, the most recent incoming freshman class received the most generous institutional packages ever offered by the college while also maximizing the available financial resources of the institution to provide those incoming students its highest quality education.

The authentically data-driven decision of this one college runs counter to the consensus narrative about the “limits” of tuition discounting, and credit rating organizations’ receptivity for of its decision remains to be seen. The complications created by the free submission of “data” to financial entities with no discernible expertise in higher education research, nonetheless, stands as an important marker in my knowledge of revenue growth and tuition discounting. The analysis illustrated in Figure 2 reveals the proper narrative about tuition discounting by private, nonprofit institutions over the past 25 years. Although each institution has its own “revenue maximizing point,” the college in my anecdote fits the norm for most of the nation’s private, nonprofit institutions. As such, perhaps, private nonprofit colleges and universities have successfully pursued tuition discounting strategies to maximize the available resources for their students during the past decade and that the current “stagnation” can be accorded to other market factors unrelated to tuition discount rates.

Rather than characterize tuition discounting as decline, then, have we not witnessed an era in which tuition discounting by private, non profit educational institutions should be celebrated as an era of revenue maximization and administrative efficiency that served to increase access and diversity in higher education?[4]

I do not doubt that the era of increasing tuition discount rates in the private, nonprofit sector of higher education has neared a new phase and that many institutions have approached or reached their optimal rate for revenue maximization. The derision for the practice of tuition discounting in general, unfortunately, neglects to consider that many educational leaders in the private sector of higher education during this era should be lauded for their measured and intelligent responses to the declining U.S. high school graduate population, an increasingly diverse and first-generation college population, and a more technologically-demanding labor market. Price-conscious education consumers generally have not “forced” tuition discounting on private, nonprofit higher education institutions; U.S. institutions have deployed tuition discounting to serve the unique missions and concrete market conditions of their private, nonprofit missions in order to expand access, improve diversity, and optimize expenditures for higher education in general. In effect, the arbitrary and normative limits for tuition discounting set by financial entities and news organizations rely on data freely given (if not misguidedly submitted) by private, nonprofit institutions, but nonetheless fail to provide a reliable or valid measures of the effectiveness and efficiency of revenue maximization for said institutions over the past 25 years. The colleges and universities that succumb to the desideratum of credit ratings and news agencies that counsel the reduction of tuition discount rates based on arbitrary and unscientific thresholds may likely, I suspect, be the first to fold in the current higher education market conditions – and bequeath to posterity the condemnable prognostications of their would-be financial advisers.

- Loren Loomis Hubbell, Tuition Discounting: The Impact of Institutionally Funded Financial Aid (Washington, D.C.: National Association of College and University Business Officers, 1992), 15-16. Available through ERIC at http://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED356731.↵

- Moody’s began surveying its rated US universities on tuition and enrollment expectations approximately five years ago per its January 10, 2013 release.↵

- Anecdotally, I was told that the vendor had not been asked to do such an analysis before and the institution was breaking new ground, so to speak.↵

- Public institutions, highly cited for increasing tuition and tuition discounts as well, may also provide the same benefits to low-income, minority, and freshman students: Nicholas W. Hillman, “Who Benefits from Tuition Discounts at Public Universities?” Journal of Student Financial Aid, Vol. 40, no. 1 (2010).↵