[W]e wished to recover the thoughts of early practitioners who – with an intellectual freedom and honesty to consider the possibilities of institutional research at its origins – recognized the need for an authentic institutional research apparatus to empower a scientific community for the study of higher education settings. In many respects, these institutional researchers were far ahead of their time in their consideration for the needs of their profession before the widespread existence of key technologies: student information systems, statistical software for the social sciences (SPSS), spreadsheets, visualization software, intranets, color monitors, etc., etc. In a manner, this group of peers exemplified the best principles of a scientific community when they began the process of generalizing standards and definitions, imagined technological apparatus to enable replication, and engaged in promising discourses on the research agenda of institutional research. While their vision may not have come to fruition in the ensuing years, their framework of a paradigm for institutional research as a social science remains – and is more so within reach today. Search for a Paradigm, Part II, September 11, 2015

Exchanges of Institutional Resources and Student Success

We opened this series of essays on inequality and higher education with a quote by Thomas Jefferson, founder of the University of Virginia. He distinguished between “the virtue and talents… of natural aristocracy” and “the mischievous ingredient… of artificial aristocracy” in the management of “the concerns of society,” singling out “wealth and birth” as two sources of artificial aristocracy. Simple binaries like “natural” and “artificial” once familiar to Thomas Jefferson as categories of distinction are not tenable today,[1] but the issues Jefferson identifies remain in the public discourse on the purpose and productivity of higher education: virtue, talent, wealth, birth, and inequality (“aristocracy”). Notably, without doubting the constancy of inequality, Jefferson questioned what kind of inequality best suited “man for the social state” and, more concretely, the American experiment with democracy and individual liberty.

At the outset, a plain truth is evident: the ecology of higher education directly contributes to inequality in the social state.

Accepting Jefferson’s warning that wealth and birth influence outcomes, economic and social capital allocations play a significant role in the ecology of higher education. More directly, we may infer, inequalities in the success of college students are outcomes produced by the allocation of resources for student success in the ecology of higher education. The National Association of System Heads (NASH) responsibly inquired about the ability of their institutions to perform research on “the cross-cutting issues of the day—such as the connections between resource use and student success.” This direct connection of resource allocation to student success at higher education institutions shifts the origin of unequal outcomes in student success from the college readiness of students to the student readiness of colleges. These unequal student outcomes at the institutions in the ecology of higher education sow the seeds for broader social, political, and economic inequality in a state or nation.

A second postulate notes: resource allocation and use in an ecology of higher education are the primary mechanisms to produce inequality in the social state.

In general, there is no predefined limit to the inequality higher education creates, since there is no ceiling to higher education and there is no end to higher education. Higher education refers to the collective knowledge incrementally acquired through the pursuit of higher education, to the individual knowledge personally acquired by such education, and to the diffusion of that knowledge throughout the stratified professional and technical activities of a society. In sum, higher education is extension, replication, and dissemination of knowledge — or “virtue and wisdom” to cite Jefferson. For this reason, most higher education institutions properly pursue at least three coherent and congruous missions: “producing research, providing instruction and preparing students for life and careers — all bundled together.”[2]

Together, the three missions of an ecology of higher education produce the recognizable differences in knowledge acquisition between individuals as well as generalizeable differences in knowledge acquisition in a single nation at two points in time. Always more than the sum of its institutions, higher education forms an ecology stretching from the most remote sectors of society to the most revered institutions of higher education. A set of weekly news items on higher education offers, by and large, a testament to the interactions in the ecology of higher education and the inequality fostered by higher education. Like Jefferson, these weekly news items serve as a warning that inequalities emanating from the global ecology of higher education encroach on the well-being of “the social state” of nations, states, and institutions.

A third proposition occurs: an ecology of higher education contributes inequality to the social state that may benefit or harm “the instruction, the trusts, and the government of society,” in particular, those societies constituting self-governing commonwealths.

Student success largely pertains to the replication of knowledge by individual college-goers as signified by degree completion. Institutional effectiveness indicates how well an institution of higher education allocates its resources to affect the success of its students. Numbered among the institutional resources for student success are the data, research, and (now) data science of student outcomes. Nonetheless, by the time students enter college, the ecology of higher education has already produced a great deal of inequality that influences degree completion by each cohort of entering students. Higher education institutions take actions to address and correct existing inequalities in the ecology of higher education in order to insure that college student success reflects a meritorious outcome. Consequently, the ASILOMAR II convention raises important questions about the ethical use of data and research, or data science, to address inequality in the ecology of higher education.

As noted by a conference goer, ethical research and decision-making supported by predictive analytics raises an important consideration:

“[T]he groups endorsed a vision of ‘open futures.’ [Mitchell L. Stevens, associate professor of education at Stanford] described it as ‘the idea that education should create opportunity rather than prevent it.’ In the case of a system that uses analytics to predict student success, for example, that system should not be used to prevent students from pursuing their dreams — to ‘foreclose the opportunity that students can be different people than they were yesterday…'”

The assignment of probabilities of success to students based on criteria loosely defined as “college readiness” opens the possibility for abuse of non-traditional students. If students’ predicted probability of success falls below a certain threshold in a quantifiable measure of college readiness, for an institution or in general, will the student be barred from entering college? Will institutional resources be husbanded for and reallocated to the students who demonstrate the greatest probability for success, such as those in honors programs?

The application of “predictive data” very easily can work to reinforce and produce anticipated negative outcomes among students when real resources are at stake. The question of how to apply predictive analytics to student success offers a perspective to distinguish between beneficial and harmful inequality produced by higher education for the social state of a self-governing commonwealth. If students are to have an open and equal opportunity to find success in higher education, an ecology of higher education must minimize decisions that artificially restrict or enhance the futures and opportunities of college students.

To secure “open futures” and equal opportunity in a self-governing commonwealth, institutions in the ecology of higher education therefore must estimate each student’s probability of success to be exactly 1.0 — that is, all college students are 100% likely to succeed. Thus, if an institution’s student success rate drops below 100%, the outcome indicates a deficiency in the effectiveness of the institution to deliver on the promise of the students. Otherwise, the institution will likely mistake the outcome as indication of a deficiency in the college readiness or capacity of its students.

If resource allocations and use are the processes and mechanisms for student success, the institution understands in a general way that inefficiencies in its resource utilization have contributed to ineffectiveness in its mission to deliver student success in higher education. A student succeeds when the resource allocations and use are sufficient for the student’s success and, vice versa, a student falls short of success when the resource allocations and use are insufficient for the student’s success.

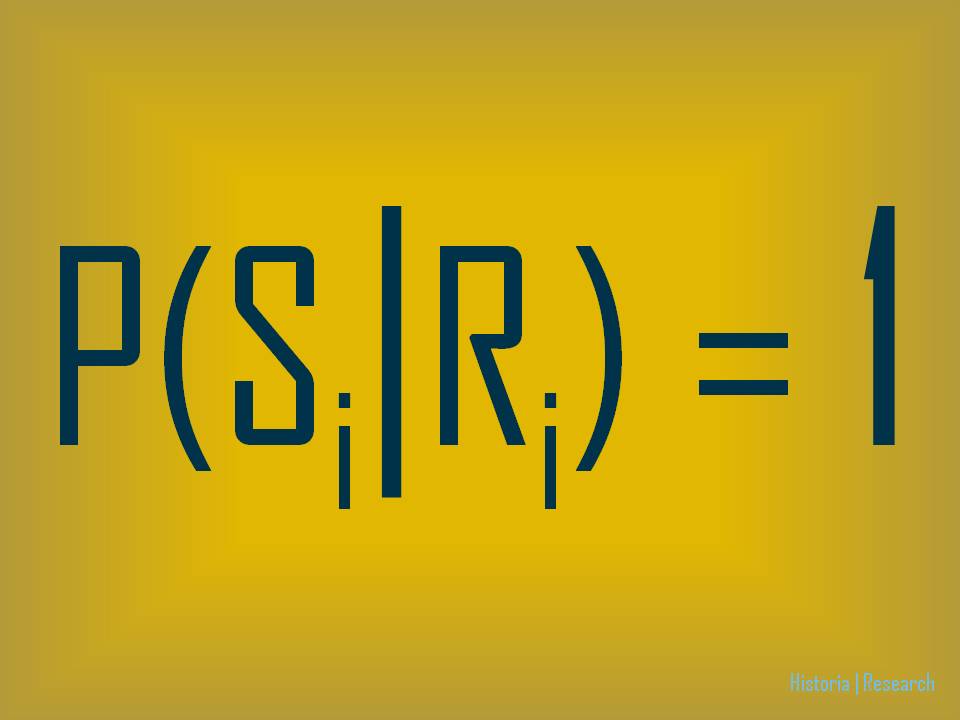

A fourth axiom provides: the probability of a student’s success given the necessary resources from the ecology of higher education approaches 1.0 or 100%. The fourth axiom also may be written as a formula, where Si is the success of student i, Ri is the necessary resources for student i:

Figure 1 | A Formula for Student Success in Higher Education

Of course, we know colleges and universities are not 100% effective in the delivery of student success in higher education. Any common measure of student success at the institutional level — for instance, student retention or graduation rate — quickly confirms that many college students do not realize their estimated probability of success in higher education.

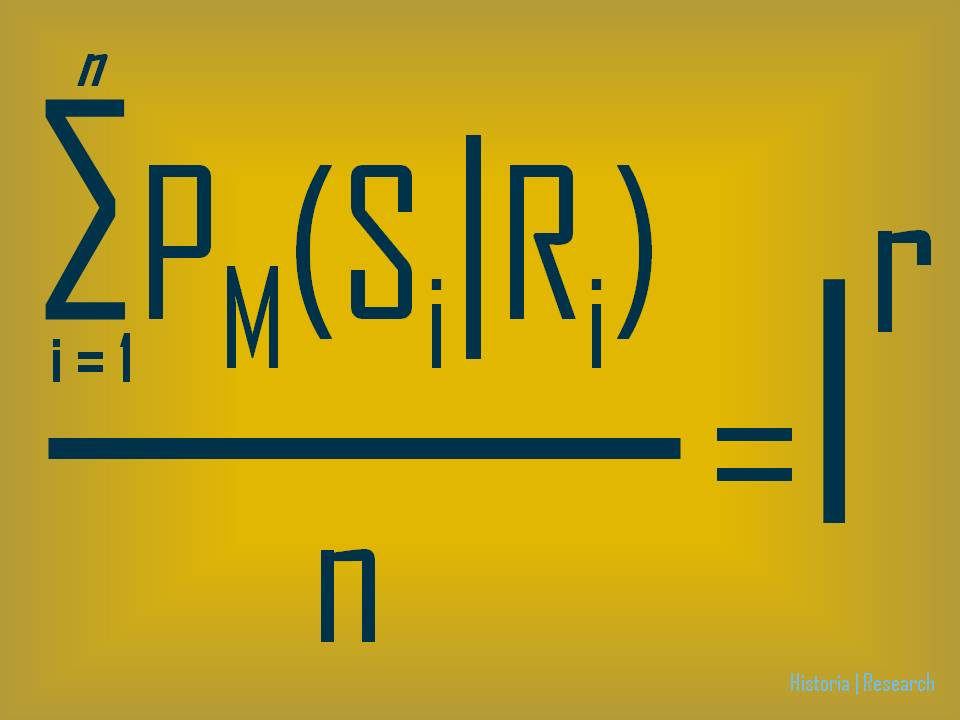

The rate of successful student outcomes, broadly defined, thereby provides a measure for the overall institutional effectiveness of each college or university. If student i at resource level i does not meet the measure of success, the measured probability of student success at the resource level i equals 0. If student j at resource level j meets the measure of success, the measured probability of student success at the resource level j equals 1. If we sum the measures of student success at the varying resource levels for all students at an institution, and divide by the total number of students at the institution, we obtain a standardized formula for the institutional effectiveness of the college or university on that measure of student success.

Additionally, the measurement of institutional effectiveness is, in essence, a formula regarding the efficient allocation of resources to meet the discrete resource needs of its students. For each student the institution allocates a sufficient level of resources, the institution records the realization of expected student success. For each student the institution allocates an insufficient level of resources, the institution records a deficit of expected student success.

A fifth theorem adds: an institution’s rate of student success on a selected metric is, in the final analysis, a measure for the efficiency and effectiveness of its allocation of resources to the student body as a whole.

This also may be expressed as a formula of summation for student success at an institution, where n is the total population of students in the test of student success, Pm is the measured probability of success (0 or 1) for student i in the population of students at resource level i, and Ir is the rate of success for the institution. For example, if 67 students from a population of 100 students total receive enough resources to achieve success on a certain measure, the institutional effectiveness for that measure is a student success rate of 0.67.

Figure 2 | A Formula for Institutional Effectiveness in Higher Education

At this stage, notably, the notion to link institutional resource allocations to student success intersects with a body of scholarship, Social Resource Theory (SRT).[3] SRT “extend[s] the notion of exchange to include all interpersonal experiences…” SRT suggests there are several “different types of transactions,” above and beyond the common framework of economic transactions, involving several different resource classes with unique transactional attributes.

The original statement on SRT defines six resource classes: Love, Status, Information, Money, Goods, and Services. For instance, as a resource class for interpersonal transactions, “Love” is “an expression of affectionate regard, warmth, or comfort.” At an institution of higher education, the resource class Love may be found in a student’s reported sense of belonging on a survey or in a student’s action to engage with faculty outside of the classroom. Likewise, Status may be conferred by an institution to its students in the form of academic reputation or course grades. These interpersonal exchanges often entail multiple social resource classes, such as the exchange of tuition and fees (Money) for instruction and enlightenment (Information), but also for grades and degrees (Status).[4]

In the SRT framework, the ecology of higher education obviously encompasses a complex set of exchanges involving different social resources classes and numerous agents. For a student attending an institution of higher education, however, if we follow the linkage between resources allocation and success to a logical conclusion, transactions may be boiled down to exchanges of institutional resources for student success.

In addition, SRT provides a framework to account for both negative and positive social resource exchanges for students at an institution of higher education. In our two-student institution example from Part II, an honors program student attends on scholarship and pays no tuition and fees ($0 per credit), while the non-honors student pays tuition and fees much closer to the list price ($800 per credit). In addition, the institution allocates $600 per credit for the instruction of the honors program students, but only $200 per credit for the instruction of the non-honors program students. The discrepancy occurs because the institution has awarded differing amounts of Status (“college readiness”) and Services (“honors program”) to the two students at the time of admission, which in turn determines how much tuition and fees (Money) each student pays out-of-pocket to attend the institution. The tuition and fee revenue (Money) is subsequently converted by exchange into differing levels of education (Information) and engagement (Love) from faculty.

The allocations of the several classes of social resources quickly adds up in the favor of the honors student who receives far more social resources at no cost than the non-honors student who pays Money for a fraction of the total social resources at the institution. In our example, we expressed the resource allocations entirely in terms of Money to show that student 1 made (+)$600 per credit in resources (R1) in the exchange, whereas student 2 (non-honors), lost (-)$600 per credit in resources (R2) in the exchange. As evidenced in the example, the social resource exchanges between an institution and its students vary widely.

If we use fall-to-fall retention as a measure of student success, and student 2 left the institution before the next fall while student 1 persisted and returned, the institutional rate of student success (Ir) will be 0.50 (or, 50%). In the “college readiness” paradigm, the institution will pat itself on the back for wisely withholding an award to the non-honors student equivalent to the honors student, since clearly the non-honors student was not “college ready” and/or not “engaged in college.” Alternatively, however, the simple fact may be that student 2 experienced his or her interactions with the institution as a negative encounter and student 1 experienced his or her interactions with the institution as a positive encounter.

Thus, rather than rationalize that some students are prepared to succeed and other students are not prepared to succeed at the time of college entry, the simplest answer may be that, in this particular ecology of higher education, college students with institutional resource allocations R1 (+$600 per credit) are infinitely more likely to succeed (100% v. 0%) than college students with institutional resource allocations R2 (-$600 per credit).

This, of course, is an unsustainable ecology of higher education because the honors student has no non-honors students to pay for his or her education after the first year of college. In order to pay for the honors student’s second year of college ($600 per credit hour), the institution must recruit or retain another non-honors student to the institution to pay $800 per credit tuition (Money) for $200 per credit services (Love, Information, Services, and Status). Likewise, a third and fourth non-honors student must be recruited or retained in order to educate the honors student in his or her junior and senior year.

After four years, one honors student becomes a college graduate, while four non-honors students become college non-completers. Thus, the institution achieves a 20% graduation rate, another measure of student success, and congratulates itself on the efficacy of its admission and financial aid award practices for honors students. Even so, per the formula for student success, non-honors students will quickly recognize that the institutional system in the ecology of higher education favors one honors student’s completion and does not deliver anticipated outcomes for non-honors students. Eventually, non-honors students will cease to provide all of the monetary social resources to the ecology of higher education in exchange for a paucity of non-monetary social resources.

As a matter of sustainability, institutions must offer a level of social resources to a percentage of non-honors students that holds off the crystallization of a legitimation crisis among non-honors students who may refuse to enroll in higher education (i.e., to withhold monetary social resources from institutions).

Assume, then, a resource allocation k (Rk) that produces a 67% freshman retention rate (i.e., success rate) for non-honors students and that the 67% success rate meets the criteria for non-honors students to provide monetary social resources to higher education for at least one year (a legitimation equilibrium point). In the interest of clarity for our example, assume also that Rk equals -$200 per credit of social resources as expressed in monetary resources. At $800 per credit tuition, the institution need only recruit 3 non-honors students paying $800 per credit tuition in return for $600 per credit instructional expenses (R3 equals -$200 per credit) — while reserving $600 per credit instructional expenses at no cost for an honors student (R1 remains +$600 per credit).

As an added feature, it appears that all four students receive the same social resources for instruction in monetary terms ($600 per credit). Whereas two out of three (67%) non-honors students at R3 (-$200 per credit) return for a sophomore year of higher education, 100% of honors students return at R1 (+$600 per credit), and the institution now has a 75% success rate for freshman retention: 2 non-honors students plus 1 honors student divided by 4 institutional students total.

The institutional mission to educate the honors student at no monetary cost to the honors student (or at all monetary costs to non-honors students, depending on the perspective) increases the overall institutional effectiveness of the college. In effect, however, the institutional mission fabricates additional inequality due to the manner in which resources are collected and allocated in the ecology of higher education to produce three different outcomes: honors completers, non-honors completers, and non-honors non-completers.

At this point, the previous axioms suggest that, at the student level, the connection of student success to resource allocations at colleges and universities in the ecology of higher education makes possible a comprehensive examination of the contributions of higher education to inequality. The inequality in students’ outcomes due to inefficient resource allocations that is acceptable to an ecology of higher education for the social state of a self-governing commonwealth is thereby evident in the institutional rates of student success.

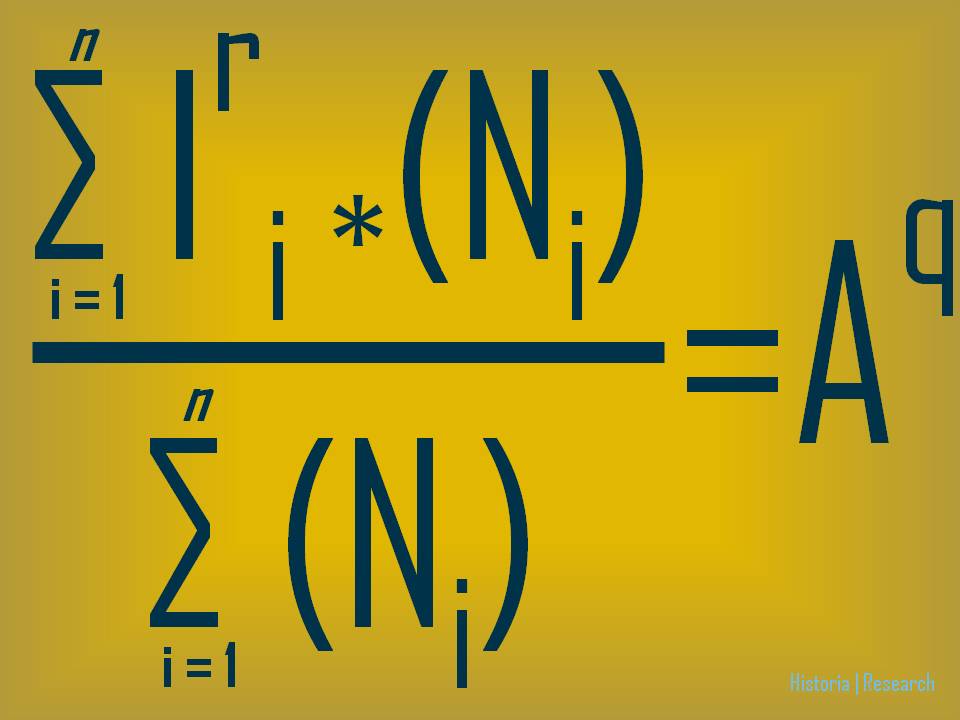

From the formulas for student success and institutional effectiveness, then, we finally arrive at a formula for the general accountability of an ecology of higher education for the delivery of success to students. A summation of the institutional rates of student success weighted by the number of students in the college population will yield a quotient indicating the rate of student success for an ecology of higher education in a state, a nation, or internationally. This measure, in effect, is an accountability quotient representing the equity of resource allocations toward beneficial outcomes on a measure of student success in an entire ecology of higher education.

This affords a sixth axiom: the accountability of an ecology of higher education to the students in its domain may be expressed as a quotient indicating the share of all students who received a sufficient share of resources to achieve success at institutions of higher education.

Again, the finding may be expressed as a formula, where Iri is the rate of student success for institution i, Ni equals the student population for institution i, n is the total number of institutions in the ecology, and Aq is the resulting accountability quotient:

Figure 3 | A Formula for Accountability for an Ecology of Higher Education

From these six propositions, we may conceive the exchanges between social resources and student success as an ecological system to contribute to the social, political, and economic inequality in a state, in a nation, and internationally. In particular, the social resource allocations at institutions in the ecology of higher education are the primary mechanisms to foster inequality in support of a desired social state, such as a self-governing commonwealth, or representative democracy, as Thomas Jefferson had in mind. Further, in a democratic ecology of higher education, institutions recognize each individual’s open future and equal opportunity to realize success given the necessary social resources — the formula for student success. When an institution fails to deliver the anticipated success of its students, the difference in the predicted and actual success of the institution’s students measures the effectiveness of the institution in serving its mission — the formula for institutional effectiveness. Lastly, the extent to which institutions deliver the anticipated student success indicates the overall accountability of an ecology of higher education to its students — the formula for accountability.

From the combination of inequality, social resources, and higher education, the contours of a paradigm for the study of institutional effectiveness in higher education come into focus. The proposition that higher education directly contributes to inequality allows institutional research scholars to pose significant questions to investigate empirically and to enlarge the overarching conceptual framework of the ecology of higher education. The items that pass as a class of facts (institutions, social resources, student success, outcomes, etc.) permit methods to directly investigate research questions and provide reasoning for coherent explanations about the effectiveness of institutions in an ecology of higher education. Lastly, a standard formula for student success enables researchers, practitioners, and agents to replicate and generalize knowledge about the allocation of social resources, encouraging the disclosure and scrutiny of the general accountability of an ecology of higher education to its students.[5] In short, the six propositions open up a program of research and scholarship, under the direction of professional administrators and scholars, to study exchanges of social resources for student success in an entire ecology of higher education.

- Thomas Jefferson, who enslaved African-Americans in Virginia, obviously had a venal and fallacious distinction between “natural” and “artificial” aristocracies. On one hand, he demonstrates personally that the concept of “natural” aristocracy is easily corrupted in order to create an artificial aristocracy in the social state. On the other hand, he also personifies how one artificial aristocracy poisons the social state of America with the mischievous ingredients of white male supremacy and race slavery. See http://www.npiamerica.org/research/category/what-the-founders-really-thought-about-race.↵

- Quote from Julia Freeland Fisher, “The High Cost of Free College,” on on KBZK.com, accessed on August 3, 2016.↵

- See Kjell Tornblom and Ali Kazemi, eds., Handbook of Social Resource Theory: Theoretical Extensions, Empirical Insights, and Social Applications (softcover, 2014).↵

- Edna B. Foa and Uriel G. Foa, “Resource Theory of Social Exchange,” in Handbook of Social Resource Theory: Theoretical Extensions, Empirical Insights, and Social Applications (softcover, 2014), edited by Kjell Tornblom and Ali Kazemi, 15-32.↵

- The paragraph reflects terminology from the National Resource Council, Scientific Research in Education (2002).↵