1 | One Hundred Years of “Institutional Research”

“[T]he university is, in usage, precedent, and commonsense preconception, an establishment for the conservation and advancement of higher learning, devoted to a disinterested pursuit of knowledge. As such, it consists of a body of scholars and scientists, each and several of whom necessarily goes to his work on his own initiative and pursues it in his own way. This work necessarily follows an orderly sequence and procedure, and so takes on a systematic form, of an organic kind. But the system and order that so govern the work, and that come into view in its procedure and results, are the logical system and order of intellectual enterprise, not the mechanical or statistical systematization that goes into effect in the management of an industrial plant or the financiering of a business corporation.” | Thorstein Veblen, The Higher Learning in America, 62–63

Prior to the 2015 Annual Forum of the Association for Institutional Research (AIR) in Denver, Colorado, I began to question why it was that an association led by self-professed experts in improving data-driven decision making and the first-year experience had little evident impact on American higher education and the outcomes of college freshmen. To my recollection, in the prior five years, neither the regional nor national associations for institutional research led substantial efforts to marshal the nation’s institutional researchers for a rigorous, coordinated study of freshman student success. In Veblen’s description of academic work, this meant that institutional research had not progressed toward “a logical system and order of intellectual enterprise” in its studies of the first-year college experience or freshman retention. The absence of “an orderly sequence and procedure” for research consequently precluded the possibility for institutional research to evolve into a “a systematic form, of an organic kind,” on what works for the higher education of college freshmen.

That is not to say there were no sessions regarding data-driven decision making on freshman retention. For instance, from 2010, I recall a presentation on the use of data analytics to identify “students at risk” by the institutional effectiveness office at a Research I university. When asked to explain how the university community received the new data-driven insights, however, the executive of the office acknowledged that there was little-to-no collaboration with the other units at the university. While the presenters claimed to have produced an analytical model that other institutional researchers may adopt to good effect, the initiative had not moved beyond the exploratory phase of “mechanical or statistical systematization” at their own campus. That is, there was no empirical evidence that the data or model presented had a non-spurious, or causal, relationship with student outcomes. Today, nearly ten years later, that same institution’s graduation rates have increased only 5 percentage points from 49% to 54%—again, not enough to claim significant improvement given that today’s universities enroll the most college-ready generation in American history.

While I attended the usual gamut of concurrent sessions in 2015, I recognized that institutional research lacked one significant feature common to other professions: an academic discipline. Behind the podiums, many of the same faces from the prior five years shared their latest insights into data-driven decision making and the first-year experience, as well as the role of institutional research in both, despite the fact that these higher education scholars’ previous presentations to practitioners had no material impact on freshman retention or other common measures of institutional performance and effectiveness for more than five years. The Forum offered its usual bromides to “high-impact practices,” including at least a dozen sessions on the annual National Survey of Student Engagement—despite mounting evidence of its dubious value for improvements to student outcomes.[1] As a whole, the sessions failed to add up as disciplinary knowledge “for the conservation and advancement of higher learning” or offer much about the application of institutional research to institutional effectiveness directly.

One session, “Preview of a Statement of Aspirational Practice for Institutional Research,” organized and delivered by the Association for Institutional Research (AIR) leadership, proved modestly illuminating. Described as an introduction to “an aspirational vision for data and decision support that acknowledges the disruptive innovations already occurring in the field of institutional research,” I walked away with the clear understanding that the leadership of the national association regarded institutional research as a commonsense practice. The presentation on aspirational practices spoke to “the campus-wide function of institutional research” and focused on the “need for institutions to build the data literacy skills of employees outside of the traditional IR [Institutional Research] Office.” In other words, the “function” of institutional research was too centralized and too professionalized within offices of institutional research.[2]

To be sure, I have nothing against commonsense solutions, but the organization of a profession around the concept and application of common sense entails certain limitations on the direction and development of practitioners’ expertise. Foremost, there is no pretension to the accumulation of knowledge like an academic discipline or science. This realization explained why the typical format of an AIR Forum session deliberately avoids theory development or claims to contribute to a general body of knowledge. Most sessions explicitly present techniques or studies at one institution that the presenters anticipate may be emulated at other institutions—with the obligatory caveat, as common sense dictates, that the technique or study be modified to suit each particular (unique) institution. In short, the Forum as a whole suggested that the association’s scholars fail to adhere to a discipline—standards of scholarly rigor, replicability, and empirical evidence—to validate the methods they recommend to practitioners.

Recently, college executives have expressed deep skepticism for the capacity of institutional researchers to improve student success and they now advocate outsourcing student success initiatives to for-profit vendors of data science. A jarring report by the National Association of System Heads (NASH), following a study of institutional research offices in the nation’s public systems of higher education, concluded, “The overall ability of IR offices to use data to look at issues affecting many of the cross-cutting issues of the day—such as the connections between resource use and student success—is nascent at best.” In response to the 2014 NASH report, the AIR acknowledged, after fifty years of stewardship by its leadership, “[T]he current function of IR [institutional research] is not clearly defined, and the future path of IR [institutional research] is unknown.” To rectify the plight of the profession for its four thousand members, the association launched yet another survey of offices of institutional research at colleges and universities across the nation in its effort to draft statements of aspirational practices for the future of institutional research, “The Statement of Aspirational Practice for Institutional Research.”[3]

In this chapter, I briefly recount the origins of institutional research as the scientific study of higher education and provide new evidence for the decline of the profession after the organization of its national association in 1965. At the time of Veblen’s publication in 1918, the scientific study of higher education gained traction following the formation of the first centralized office of institutional research at the University of Illinois. In the fifty years following, institutional research enlarged its area of research expertise, in “an orderly sequence and procedure,” to include many facets of higher education in American society. By the 1960s, statewide institutional research produced generalizable knowledge about systems of higher education that fostered strategic and master planning.

These advances, however, also portended the transfer of some administrative decision making about American higher education beyond local institutional control. A vocal, if small, cadre of scholars sought to forestall the professionalization of institutional research and the statewide coordination of higher education systems. To use Veblen’s terminology, the critics rejected institutional research’s claim to being “a systematic form, of an organic kind” and denounced institutional research as “the mechanical or statistical systematization” foisted on higher education by a managerial revolution. A consensus paradigm about the study of higher education grew out of the work of critics who recast institutional research as a facet of business enterprise and, in their capacity as leaders of the national association for institutional research, hindered “the conservation and advancement of higher learning” about how colleges work.

A Movement for Universities to Study Themselves and to Plan Consciously for Changes within Themselves

The first half of Outsourcing Student Success uncovers the path-breaking institutional researchers who endeavored to establish and advance the scientific study of higher education. Using the framework of scientific paradigms from the work of Thomas Kuhn, this history of institutional research explores how the new approach to the study of higher education proved successful “in solving a few problems that the group of practitioners [had] come to recognize as acute.”[4] In the early twentieth century, the biggest challenges appeared to be the organization and self-study of universities—the large conglomerates of academic programming that Veblen saw as a threat to higher learning. Within decades, the limits of self-study at one institution for the accumulation of knowledge about higher education became evident and the complexity of the phenomena of higher learning more fully understood to institutional researchers. In response, a small cadre of institutional researchers across the nation, initially dedicated to the study of their respective institutions, reached out to each other through publications and meetings to discuss their successes and challenges. The first fifty years of institutional research culminated in the coordination of studies between universities, planning for statewide systems, and the first steps toward the formation of an association for the fledgling profession.

The history of institutional research begins with the first centralized office (“bureau”) of institutional research established at the University of Illinois (UI) in 1918. In 1938, after twenty years of research activities, Coleman R. Griffith provided a firsthand account of accomplishments by the UI Bureau of Institutional Research for the Journal of Higher Education. Griffith was a psychologist who is regarded as the “father of sports psychology,” but also could be regarded as the father of institutional research. He conducted a number of unprecedented studies for UI that largely have been neglected by later scholars of higher education.

According to Griffith, prior to World War II, the university conducted research on academic program reviews and established benchmarks for the performance of programs, including longitudinal studies on the unit costs and student credit hour productivity of academic programs. The university studied faculty loads by rank and class level as well as the quality of teaching as measured by student learning outcomes. And, his Bureau of Institutional Research performed analyses on resource allocations and utilization, including classroom space capacity and enrollment projections. Most importantly, however, his decision to publish a review of his bureau’s activities shined a light on the little-known movement to establish more rigorous standards for research about higher education.[5]

Only a dozen or so universities established similar offices during these years, largely at Midwest universities accredited by the Higher Learning Commission like the University of Illinois. The Great Depression and Second World War then seem to have deterred the widespread adoption of centralized institutional research offices until the mid-to-late 1950s.

Four publications within a span of ten years reignited interest in the budding field and restored interest in the scientific study of higher education. In 1954, Ruth E. Eckert co-authored a comprehensive retrospective on the institutional research she designed and conducted at the University of Minnesota as a former director of its bureau and as a faculty member on its associated committee. In 1955, the University of California system released its statewide institutional research study, the California Restudy, on the impending demand for higher education among California citizens and its Baby Boomer population. In 1960, the American Council on Education (ACE), the association representing the nation’s college presidents, published a report on the integral role of institutional research in quality improvement in higher education in general. Lastly, in 1962, institutional researchers organized the first open forum for practitioners across the country and published a comprehensive volume on the methods of the field, Basis for Decision.[6]

Each of these works demonstrated the progression of institutional research in a significant way and elevated the public discourse on higher education administration. First, Eckert and the University of Minnesota made explicit the potential replication and publication of institutional research studies for peer review and public scrutiny. Second, The California Restudy demonstrated that colleges and universities may be examined for their extrinsic or outward qualities in order to rationalize, organize, plan, and coordinate the delivery of higher education as a state system. Third, the ACE report brought focus to the intrinsic or essential characteristics common to higher education in general that may explain the quality or effectiveness of particular institutions. Lastly, as one contributor to the 1962 collection of essays summarized, institutional research led “a movement…for universities to study themselves and to plan consciously for changes within themselves.”[7]

The advances as a whole established that higher education may be studied for its qualitative and quantitative phenomena, as systems exhibiting causal and/or organic relationships between components (institutions), and as complex processes that nonetheless featured discernible mechanisms to promote and plan for incremental quality improvements. In short, higher education may be studied as a system, rationalized as an administrative process, and coordinated to pursue certain objectives as determined by state, regional, and national priorities.

By the early 1960s, institutional research seemed to be at the threshold of forming into a social science for the study of higher education. As the National Science Foundation stated several decades later, “[I]t is the scientific community that enables scientific progress.”[8] Institutional researchers appeared poised to take this final step toward formal community building for an academic discipline. They organized the first national forums for practitioners and scholars in the early 1960s, resulting in the formation of a national organization in 1965, the Association for Institutional Research. By all appearances, the profession moved forward and seemed likely to add the study of higher education to the list of academic disciplines organized by social scientific principles and methods.

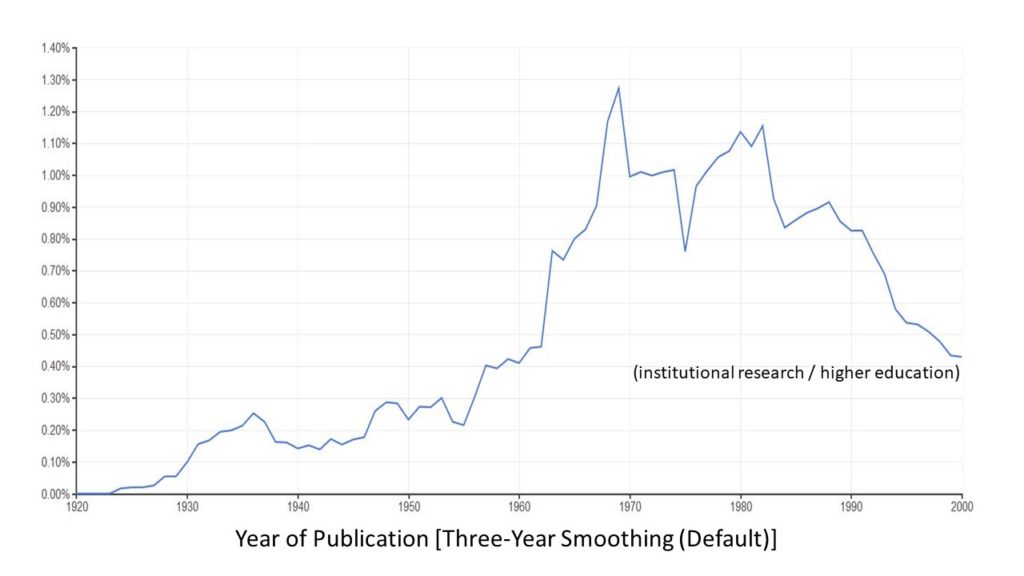

To illustrate the origins and increasing prominence of institutional research in the public discourse on higher education, the Ngram Viewer for the digitized archive of Google Books provides data visualizations that record the incidence of “institutional research” during the past one hundred years. The Ngram Viewer offers a measure of the frequency for a term or phrase in the entire digital library and with the help of operators, such as the divisor (“/”), may isolate “the behavior of an ngram with respect to another.” For example, the incidence of “institutional research” may be pegged to the incidence of “higher education” to account for variations in the larger public discourse on college and universities.[9]

Although the reliability and validity of the Google Ngram Viewer for studying “the rise and fall of words and ideas” remains an open question, the tool’s reliability and validity may be enhanced when paired with extensive historical research on a specialized subject. For instance, the historians who wrote The History Manifesto, a survey of historiographical trends during the past fifty years, used the Ngram Viewer to track the usage of “short-termism,” a neologism specific to historical research and writing originating in the late 1970s. Similarly, Ngram Viewer can produce a trendline visualization for a phrase like “institutional research,” a neologism for the study of higher education, that provides evidence for the era in which the phrase came into existence and the trends in its usage subsequently.[10]

For instance, the AIR later invented a history of the profession’s origins that traces its earliest practices to Yale in the 1700s, a date recently adopted by the Chronicle of Higher Education.[11] A search using the Ngram Viewer clearly shows to the contrary that “institutional research” does not gain currency until after 1920. While there are a few instances of the phrase, it occurs out of context with modern usage after 1920. For example, in a 1903 article on the most effective use of endowments for scientific research, a lone commentator uses the phrase to describe academic studies and scholarship conducted in any scientific discipline at a university. Of course, data visualization does not definitively resolve whether institutional research originated in the 1700s or 1900s—skeptics may argue that the new phrase describes practices that have not fundamentally changed for over 300 years—but the presumption that colleges have engaged in this specialized type of study since colonial times runs the greater risk of an anachronism: the transposition of modern scientific principles to the historical origins of colleges in America.

Returning to the historical narrative in Outsourcing Student Success, the Ngram Viewer offers further evidence for its main argument about the origins and outcome of the profession. As Figure 5 shows, the phrase “institutional research” gains credence in the American English lexicon only after the first centralized office organized at University of Illinois. Subsequent dates marking periods of ascendancy for the phrase coincide with the first institutional research publications analyzed at length in my work.[12]

- Figure 5 | Google Books Ngram View of Institutional Research Relative to Higher Education

Griffith’s publicization of his efforts at the University of Illinois coincides a growing interest in institutional research during the 1930s. Incidence of the phrase dips with the start of the Second World War, but then begins to ascend in the years immediately after the war. The publication of Ruth E. Eckert’s retrospective on the office of institutional research at the University of Minnesota and the statewide 1955 California Restudy sparked a new era in the public discourse when the value of institutional research for college and statewide planning became better known. Then, in the early 1960s, the ACE endorsed institutional research as an essential process for quality improvements in higher education and practitioners’ forums led to collaboration on Basis of Decision, a work that introduced theoretical considerations in general and peer reviewed articles on a variety of specific research subjects under the purview of the scientific study of higher education.

As I demonstrate in the first half of the historical narrative, the primary innovation of institutional research—the first centralized offices—ushered in a period marked by the application of scientific principles to the study of systems of higher education. This innovation in and of itself required public discourse about institutional research methods and higher education in general as each of the publications noted above significantly advanced community-building among scholars and practitioners. The increasing frequency of the phrase, especially between 1955 and 1964, attests to the revolutionary potential posed by a new professional field engaged in the scientific study of higher education systems across the United States. As a capstone to the spirit of scientific research, the pioneers of higher education research and scholarship formally organized the Association for Institutional Research. Soon after, however, the public discourse for “institutional research” reached its apex and declined steadily for thirty years, indicating that the budding social science had failed, or been derailed, which I took to be the focus of the second half of Outsourcing Student Success.

A Function with a Minimum of Specific Implications for Organization

The relative frequency of institutional research to higher education takes a decided turn after 1968–69. In 1966, in the first noteworthy salvo against the profession, Francis E. Rourke, an established critic of statewide research and coordination, enumerated the many “perils” of institutional research to individual colleges and universities in a coauthored screed against the “managerial revolution in higher education.” The reversal in fortune for institutional research, however, more closely coincides with the efforts of Paul L. Dressel and Joe L. Saupe to redefine institutional research in a way that dismissed the scientific potential of the profession and diminished its relevance for the study of higher education.

Joe L. Saupe, from the University of Missouri, served as the fourth president of the Association for Institutional Research—the same year the relevance of institutional research in higher education discourse suddenly reverses and begins its fifty-year decline. In his presidential address at the annual Forum, Saupe broke with an emerging tradition at the Forums where the current presidents outlined next steps for the development of the profession. Instead, he claimed, the prior statements or vision “could not be topped.” He later cowrote the first AIR white paper on institutional research released in 1970, “The Nature and Role of Institutional Research,” in which he stated that institutional research is a “function [that] should not be expected to produce knowledge of pervasive and lasting significance.” Concurrently, his former mentor, Paul L. Dressel asserted that institutional research required on the job training—that could not (and should not) be taught by an academic program—at one particular institution, requiring only internal (private) discourse and direction. Together, the two former institutional researchers cultivated a consensus paradigm for institutional research in the early 1970s.[13]

By “consensus paradigm,” I intend to convey the idea that the nature and role of institutional research in colleges and universities became a settled matter among scholars of higher education. In fact, the consensus paradigm for institutional research coincided the emergence of higher education as a field of study. Indeed, many of the early leaders for the Association for the Study of Higher Education (ASHE) in the late 1970s had also participated in the formation of the Association for Institutional Research (AIR) a decade earlier. Although the field of institutional research traces its origins as a modern profession to the early twentieth century when the first centralized offices organized, the roots of the consensus paradigm for institutional research arose from the organization of higher education as a discipline and professional organization fifty years later.

The consensus paradigm for institutional research is summarized in four basic priorities first proposed by Dressel, a scholar who participated in the formation of AIR and ASHE, and Saupe, his former subordinate and associate who became a lifelong leader and contributor to the AIR. As I summarized:

Their writings set down four fundamental tenets for the practice of institutional research that influenced the practice and organization of institutional research in subsequent years. First, institutional research is “a function” of administrative staff (Dressel and Saupe). Second, “institutional research is different from the research of faculty members” (Dressel), and they warn not “to confuse institutional research, as we view it, with the more basic research on higher education” (Saupe). Third, the purpose of institutional research is “to probe deeply into the workings of [a single] institution” (Dressel); thus, institutional research is “specific and applied…and should not be expected to produce knowledge of pervasive and lasting significance.” (Saupe). Fourth, as “a function,” institutional research may be performed by nonspecialists and faculty committees (Dressel) and, generally, “carried on in institutions whether or not individuals or organizational units are specifically assigned to institutional research” (Saupe). In a short time, the consensus paradigm appeared to be a settled question in the subsequent literature under the control of scholars of higher education and the Association for Institutional Research.[14]

Despite recent efforts by the AIR to recast its direction as a “new vision,” this consensus paradigm continues to define the practice of institutional research in the study of higher education.

Returning to Figure 5, use of the phrase “institutional research” stagnates after the interventions of Dressel and Saupe. The oscillations in frequency of the phrase reflect in part the negative references to institutional research as a function and as a contrast to scholarship on higher education during the period. In 1978, Cameron Fincher, at University of Georgia, labeled the contentious redefinition of institutional research as “predictable crises” for a staff function in higher education. At the end of the decade, one college executive described institutional research as an “evolving misnomer” unworthy of the designation “research.” Similarly, one of the first institutional researchers who contributed directly to original statewide research in the 1950s noted the absence of historical memory for the foundations and pioneers of the field. Many others vaguely sensed the paradigm shift in institutional research but few, if any, comprehended the reasons why.[15]

In 1980, the AIR released Saupe’s second iteration of his vision, “The Function of Research,” and a new decline in the prominence of the phrase ensued. Subsequently, between 1985 and 1991, Fincher and other scholars in higher education worked to redefine institutional research as an art, not a science. The AIR followed with its third iteration of Saupe’s vision for institutional research in 1990. In addition, Patrick Terenzini, at Pennsylvania State University and the series editor for the national association’s flagship journal, first sounded warnings about the perils of computer technology skills for the professional stature of institutional researchers. A second era of decline in the use of the phrase began, and the incidence of “institutional research” in the public discourse fell to 1962 levels by the end of the century. Within thirty years, scholars of higher education had fully reversed the relevance of institutional research and recast the scientific study of higher education as a “perilous” (and now discredited) managerial revolution in higher education. As I explored in the final half of my prior work, the tectonic shift in the paradigm for the field ended in declarations that institutional research is an art and not a science.[16]

The content and tone of the discourse suggested that institutional research had lost stature after 1965, but the Ngram Viewer evidences the increasing irrelevance of institutional research in the public discourse on higher education. Following each intervention to redefine the nature and role of the profession by the AIR and its scholars of higher education, the frequency of references to “institutional research” pegged to references to “higher education” diminishes.

By comparison, two related phrases, “college admissions” and “institutional autonomy,” have increased in relative usage vis-à-vis “higher education” since 1960 (see Figure 6). While “institutional autonomy” has an equally long history as institutional research, the phrase gains greater relevance only after the 1960 California Master Plan. Clark Kerr, the former President of the University of California System and the architect of the 1960 California Master Plan, suggests that the era of system planning marshalled opponents of statewide institutional research when it became an annual administrative requirement for colleges and universities in the sixties. Its increasingly frequent appearance in the literature on higher education coincides with the “predictable crises” of institutional research in the 1970s. Similarly, “college admissions” became less frequent at a time when institutional research significantly contributed to system and enrollment planning for the Baby Boomer generation. After institutional research entered its crisis years, however, the term again escalates in usage. By 1985, when Generation X entered college, institutional research and system planning both had fallen into disrepute, exposing the administration of higher education to the arbitrary priorities of institutional autonomy and college admissions.

- Figure 6 | Google Books Ngram View of College Admissions, Institutional Autonomy, and Institutional Research

Notably, both terms, “college admissions” and “institutional autonomy,” are far

more prevalent at the end of the twentieth century than in 1965, while by

comparison “institutional research,” despite having the stewardship of its own

national association over the same period, diminished in the public discourse

on higher education. Whatever the specific mechanisms were, the decline of

institutional research coincides with the leadership of the national

association and the emergence of higher education as a field of study with

specialists who claim to be experts about the nature and role of institutional

research as a “function.”

Defenders of the national association and the scholarly literature no doubt will point to some other explanation such as technological determinism, administrative contingencies, or systemic exigencies that decentralized institutional research and placed institutional research outside of the control of institutional researchers. Nonetheless, I emphasize the AIR’s 1970 white paper by Joe L. Saupe as the crucial turning point because the faithless redefinition of institutional research in the text irreversibly dragged the field away from its scientific origins.[17] Institutional research evolved out of self-study into a potential discipline for the scientific study of systems of higher education by the mid-twentieth century. Yet, many stakeholders in higher education wanted to shove the genie back into the bottle of self-study, including the early leadership of the new association. As the association membership rapidly grew in the 1960s and 1970s, many practitioners never learned of the early origins of institutional research and adopted the association’s priorities as the only possibility for the profession.

Within five years of its organization, the AIR’s scholars effectively recast institutional research as “within an (one) institution,” thereby distancing its members from the collective interest in multi-institutional studies of the college systems and regional associations. They claimed, “institutional research should not be expected to produce knowledge of pervasive and lasting significance,” dismissing its potential as a science for the accumulation of knowledge. They labeled institutional research “a function with a minimum of specific implications for organization,” despite the fact that the profession and association grew out of the centralized offices in university administrations. Remarkably, when the “predictable crises” in institutional research occurred every ten years, thereafter, the AIR’s leadership uncritically recycled Saupe’s vision for institutional research as a new vision for the next generation of professionals. In three separate policy papers written by its former president in a twenty-year span, the AIR papers in effect guided institutional research on a path to becoming an insular, unscientific, and undisciplined (i.e., lacking a discipline) profession with little relevance to the national discourse on higher education.

While the Ngram charts end after the first eighty years of institutional research (2000), a review of more recent literature reveals that little has changed in subsequent decades. In 2012, the AIR invited Patrick Terenzini to receive its distinguished member award at the Annual Forum. A scholar of higher education who routinely downplayed and dismissed the use of computer technologies, his address doubled down on his prior warnings about technology to institutional researchers. His keynote speech singled out “big data” and data analytics for scorn:

“[I]t is vital to IR’s utility, credibility, and respect in the eyes of faculty members and administrators that we avoid capitalizing on what’s in a database just because it’s there and just because we now have the capacity for doing ‘big data’ and ‘data analytics’ (and basking in the reflected glory of that and other analytical capacities). The danger, in my view, is that whatever we might turn up is likely to underspecify the complexity of most important problems.”

Notably, the same year that Terenzini sounded the alarm against the dangers of data science at the AIR Forum, Harvard Business Review foresaw that data science would become “the sexiest job of the 21st century.”[18] Following Terenzini’s address, unsurprisingly, the AIR’s 2014 survey of its membership found that less than twenty percent of “higher ed’s data experts,” to use the nomenclature of the Chronicle of Higher Education, anticipated that data analytics was to become more integral to their work.

In the midst of these events, the National Association of System Heads (NASH) released what arguably should be regarded as a scathing report on the scholars who have defined institutional research. In its 2014 report on the offices of institutional research at public institutions, NASH concluded: “The overall ability of [institutional research] offices to use data to look at issues affecting many of the cross-cutting issues of the day—such as the connections between resource use and student success—is nascent at best.”[19] NASH’s skepticism for the potential of institutional research offices to perform basic research functions within a system understandably resulted in its advocacy for outsourcing student success solutions to third-party, for-profit vendors of data science, to which the title of my first work alludes.

To be clear, the Association for Institutional Research had existed for fifty years to that time. In the decade prior to the 2014 NASH report, as illustrated in the prologue, the AIR leadership and scholars had no appreciable influence on the first-year experience and retention of America’s college students. They then dismissed signs of “the new day” for institutional research that entails expertise in data science and analytics on student success. In its “New Vision for Institutional Research” released in 2016, the leadership of the AIR recommitted to each of these follies, suggesting that institutional research had become too centralized in offices of institutional research and the practitioners of institutional research had become too professionalized. The consensus paradigm that defines institutional research as “a function with a minimum of specific implications for organization,” detached from scholarship on higher education, continues to dictate the ideological habits of thought and practices offered by scholars to institutional researchers.[20]

The Management of an Industrial Plant or the Financiering of a Business Corporation

For nearly fifty years, the official policy of the Association for Institutional Research advocated that institutional researchers regard the work as “a function,” with minimal regard for organization and the accumulation of knowledge, prioritized by the provincial scope of a single institution, and with intellectual tools acquired from on-the-job training. Contrary to Veblen’s characterization of what makes a university, the national organization for institutional research neglected to define or develop an academic discipline to organically accumulate knowledge and stock its professional ranks with “a body of scholars and scientists.” In short, the paradigm shift that transformed institutional research from science to art did not occur according “to an orderly sequence and procedure…[that] takes on a systematic form, of an organic kind,” as Veblen described higher learning and academic research.

Absurdly, the AIR leadership positions itself as higher education’s data experts for the improvement of decision making in academic programming and administration—while refusing to apply its putative expertise to the design and development of a discipline and academic program for its own membership. To the contrary, according to the AIR’s historical documents, institutional researchers require little formal education above and beyond what common sense and direct job experience provide or, in Veblen’s terms, “the mechanical or statistical systematization that goes into effect in the management of an industrial plant or the financiering of a business corporation.” The commonsense notion of institutional research thus serves a twofold purpose: first, it signals that practitioners of institutional research should not be regarded as experts or as having a legitimate expertise for college administration, and second, it stigmatizes institutional research as an offshoot of the culture of business enterprise that threatens faculty.

It is important on this point to maintain a clear distinction between institutional researchers as practitioners and the AIR leadership since its earliest years—the past and present scholars of higher education who regard themselves as specialists on college administration and decision making. The transformation of institutional research from an emerging social science into an art occurred under the influence of tenured faculty in academic institutes and departments of higher education at Michigan State University, University of California, University of Georgia, Indiana University, and Pennsylvania State University, to name a handful. Thus, the idea that institutional research is a domain of managerial functions which do not require a formal academic discipline originated with the discipline of higher education during the late 1960s and early 1970s—in other words, the consensus paradigm formed as a result of a hostile intervention from outside the profession by self-described scholars of higher education.

Among the many who introduced the formal distinction between institutional research and “the research of faculty members,” Paul L. Dressel continues to be cited as the final word on the nature and role of institutional research among scholars of higher education. As recently as 2015, Victor Borden (Indiana University) and Karen Webber (University of Georgia) reaffirmed the lasting value of “the more formal characterization by Dressel and associates…[who] capture well the theoretical distinctions” between institutional research and research on higher education.[21] As these two scholars bring to light, the consensus paradigm for institutional research still retains its ideological hold on the academic mind.

It is also necessary to understand that, more so, this intervention was one single facet in a larger set of priorities that Dressel and his associates set for scholarship on higher education in general. In sum, the history of institutional research reflects a larger effort by these scholars to control the direction and administration of American higher education during the past fifty years. Specifically, the scholars who actively support a framework that disassociates their own research on higher education from institutional research have effectively cut short and impeded the scientific study of higher education.

With this insight, the most pertinent lines of

historical inquiry are: Why have scholars of higher education abandoned the

principles of science for the study of higher education? Why have higher

education scholars advocated a model of college administration that adopts

inward-looking principles of business enterprise without regard for the

standardization of research methods and the accumulation of knowledge about how

colleges work? Which stakeholders have profited from the anti-scientific

ideological turn initiated by the scholarship of higher education as a field of

study? Lastly, which college-goers have been harmed by a cultural hegemony that

discourages the application of scientific principles to the study and administration

of American higher education?

Interested in learning more? See An Afterword for Readers (spoiler alert).

[1] Sarah Randall Johnson and Frances King Stage, “Academic Engagement and Student Success: Do High-Impact Practices Mean Higher Graduation Rates?” The Journal of Higher Education 89 no. 5 (2018), 753-781.

[2] Association for Institutional Research (AIR), “Data and Decisions for Higher Education,” Program Book and Schedule for the 2015 AIR Forum, Denver, Colorado, May 26–29, 2015 (2015), 35.

[3] National Association of System Heads (NASH), “Meeting Demand for Improvements in Public System Institutional Research: Progress Report on the NASH Project in IR” (March 2014), http://nashonline.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/Assessing-and-Improving-the-IR-Function-in-Public-University-Systems.pdf, 2–6. NASH released a final report echoing the same conclusions in the next year: “Meeting Demand for Improvements in Public System Institutional Research: Assessing and Improving the Institutional Research [IR] Function in Public University Systems” (February 2015), http://nashonline.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/Assessing-and-Improving-the-IR-Function-in-Public-University-Systems.pdf. The original location of these two reports changed in August, 2017. Both accessed on October 13, 2017. Earlier versions of the e-documents were accessed on March 23, 2017. “Improving & Transforming Institutional Research in Postsecondary Education,” Association for Institutional Research, accessed June 29, 2015, http://www.airweb.org/Resources/ImprovingAndTransformingPostsecondaryEducation/Pages/default.aspx.

[4] Kuhn, Scientific Revolutions, 23.

[5] Coleman R. Griffith, “Functions of a Bureau of Institutional Research,” The Journal of Higher Education 9, no. 5 (1938): 248–255; Christopher Green, “Psychology Strikes Out: Coleman R. Griffith and the Chicago Cubs,” History of Psychology 6, no. 3 (2003): 267–283; Wycoff, Outsourcing, 31–34.

[6] Ruth E. Eckert and Robert J. Keller, eds., A University Looks at Its Program: The Report of the University of Minnesota Bureau of Institutional Research, 1942–1952 (1954); T. C. Holy, H. H. Semans, and T. R. McConnell, A Restudy of the Needs of California in Higher Education, Prepared for the Liaison Committee of the Regents of the University of California and the California State Board of Education (1955); A. J. Brumbaugh, Research Designed to Improve Institutions of Higher Learning (1960); and L. J. Lins, ed., Basis for Decision: A Composite of Current Institutional Research Methods and Reports for Colleges and Universities, published as The Journal of Experimental Education 31, no. 2 (1962).

[7] I review this history in Chapters 3, 4, and 5 of Outsourcing Student Success.

[8] R. J. Shavelson and L. Towne, eds., Scientific Research in Education, Committee on Scientific Principles for Education Research, Center for Education, Division of Behavioral and Social Sciences and Education, National Research Council [NRC], (2002).

[9] “Google Books Ngram Viewer,” https://books.google.com/ngrams/info# (accessed April 4, 2019).

[10] Sarah Zhang, “The Pitfalls of Using Google Ngram to Study Language,” Wired (October 12, 2015), https://www.wired.com/2015/10/pitfalls-of-studying-language-with-google-ngram/ (accessed April 4, 2019);

[11] Donald J. Reichard, “The History of Institutional Research,” in Richard D. Howard et al., eds., The Handbook of Institutional Research (2012), 3–21; William F. Lasher, “The History of Institutional Research and its Role in American Higher Education over the Past 50 Years (Chapter 2),” in Gary Rice, ed., AIR, The First Fifty Years, The Association for Institutional Research (2011), 10–15. Lasher indicates the two coordinated to provide very similar historical accounts for the AIR. See also, Audrey Williams June, “Higher Ed’s Data Experts Face a Crossroads,” The Chronicle of Higher Education (August 31, 2017).

[12] Ngram Viewer search parameters: “‘institutional research / higher education’ between 1920 and 2000 from the corpus English with smoothing of 3.” Smoothing denotes a rolling average of +/-3 years before and after year of publication, the Ngram Viewer default setting. Similar parameters were used for all Ngram Viewer charts, terms and years varying as warranted by the analysis.

[13] Joe L. Saupe and James R. Montgomery, “The Nature and Role of Institutional Research…Memo to a College or University” (1970), accessed March 23, 2017, http://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED049672.pdf; Paul L. Dressel and Lewis B. Mayhew, Higher Education as a Field of Study (1974).

[14] Wycoff, Outsourcing, 112.

[15] Ibid., Chapter 6 (passim).

[16] Ibid., Chapter 7 (passim).

[17] Saupe and Montgomery, “The Nature and Role of Institutional Research.”

[18] Patrick T. Terenzini, “‘On the Nature of Institutional Research’ Revisited: Plus Ça Change…?” Research in Higher Education 54, no. 2 (2013), 137–148; Thomas H. Davenport and D. J. Patil, “Data Scientist: The Sexiest Job of the 21st Century,” Harvard Business Review (2012), https://hbr.org/2012/10/data-scientist-the-sexiest-job-of-the-21st-century.

[19] NASH, “Meeting Demand,” accessed October 13, 2017.

[20] Wycoff, Outsourcing, Chapter 9 (passim).

[21] Victor M. H. Borden and Karen L. Webber, “Institutional and Educational Research in Higher Education,” in Karen L. Webber and Angel J. Calderon, eds., Institutional Research and Planning in Higher Education: Global Contexts and Themes (2015), 16–27.