Institutional researchers oversee a bounty of information stored in student information systems and enterprise resource planning systems of colleges universities. Yet, there is little guidance to enable IR practitioners to collectively organize their respective institutions into a large array for the systematic measurement of student success and “what works” in higher education. Instead, technology infrastructure for institutional research is implemented at each institutions as if the particular context of an institution requires a unique solution. As ad-hoc demands increase, IR practitioners’ workloads grow under the weight of student surveys and one-time projects to capture the conditions and commitments of students at a single point in each student’s college career. Institutional Research and Science: The Parameters, January 27, 2016.

Equity and Higher Education

As we noted in Part VIII of Honors of Inequality, and as evidenced by historical record of on higher education statistics for national states, no nation delivers on the potential of universal student success in higher education.

The replication of knowledge — and accountability for student success — nonetheless holds an asymmetrical priority in every national ecology of higher education. Without the replication of knowledge — or, the success of students to study and learn what others in the social state have discovered previously — an ecology of higher education will fail to extend the knowledge of higher education with new discoveries and will be unable to disseminate the knowledge of higher education to an ever-growing empire in the social state. Each ecology of higher education in a democratic social state, therefore, seeks to define accountability for student success that sustains the ecology and the social state, given the circumstances carried forward from the past.

A brief consideration of U.S. President Barack Obama’s 2020 College Completion Goal for the United State and of OECD national college attainment rates serve as examples of our proposition.[1]

In 2009, President Obama challenged Americans to become the nation with “the highest proportion of college graduates in the world…” by 2020. Foreshadowing the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA), he asked “every American to commit to at least one year or more of higher education or career training…” in anticipation that the labor market will increasingly require post-secondary education or training in the future.

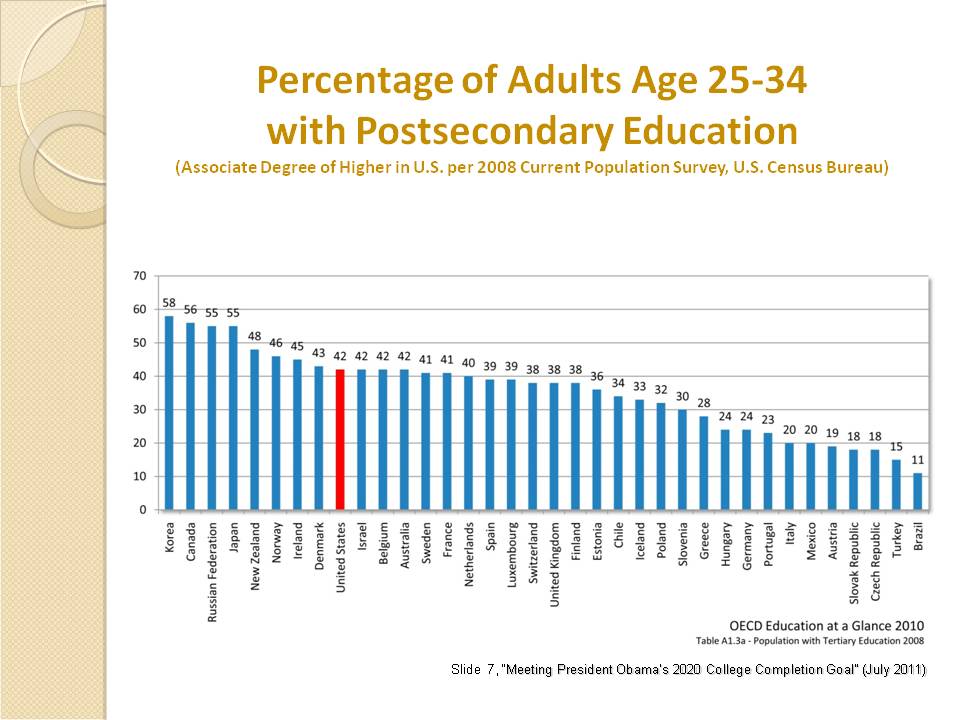

The college attainment rate for 25 to 34 year old Americans, however, stood at only 42% at the time. To translate his proposal into an accountable goal, President Obama called on the nation’s higher education and post-secondary institutions to educate 8 million additional Americans (beyond projected growth) who will reach age 25 to 34 years in 2020. At that target, the U.S. college degree attainment rate will increase to 60%, two percentage points higher than the most educated population (South Korea) at the start of the decade (see Figure 1).

Figure 1 | Percentage of Adults Age 25-34 with Postsecondary Education (U.S. DoE Chart)

In effect, President Obama positions the college attainment rate of Americans aged 25 to 34 years as a standard for the accountability quotient (Aq) in the U.S. ecology of higher education. Notably, the U.S. goal is linked generally to the ten-year cohort of Americans born between 1986 and 1995, rather than a percentage of college-goers, acknowledging that the ecology of higher education is accountable for the postsecondary educational attainment of every American citizen. That generation was aged 15 to 24 in 2010, his goal was an appeal to young Americans to demand more from the the ecology of higher education as much as it was an agenda set for higher education institutions.

At the same time, the figures and the U.S. goal verify that, historically, American citizens (and most citizens from the OECD nations) do not expect their national ecology of higher education to deliver success to every student in each generation. At the time President Obama announced his goal, the accountability quotient for the American ecology of higher education did not guarantee that a majority of each American generation could attain the benefits of a college degree seven or more years after high school age (Aq = .42). Despite the President’s suggestion that every student could invest in 1 year of college or other postsecondary training, he modestly set the U.S. goal for 2020 at 60% (Aq = .60) of its 25-34 year old population to earn a tertiary degree.

In practice, the U.S. and other OECD nations tend to offer a minority of its citizens the social resources necessary to attain a tertiary degree by the age of 34. As a question of social resource allocations in an ecology of higher education, then, the accountability quotient defined by President Obama provides a means to measure equity in a democratic ecology of higher education. This is true regardless of whether sufficient social resources to educate the entire student population are available (Aq = 1.0). Two simple, hypothetical examples will demonstrate the point.

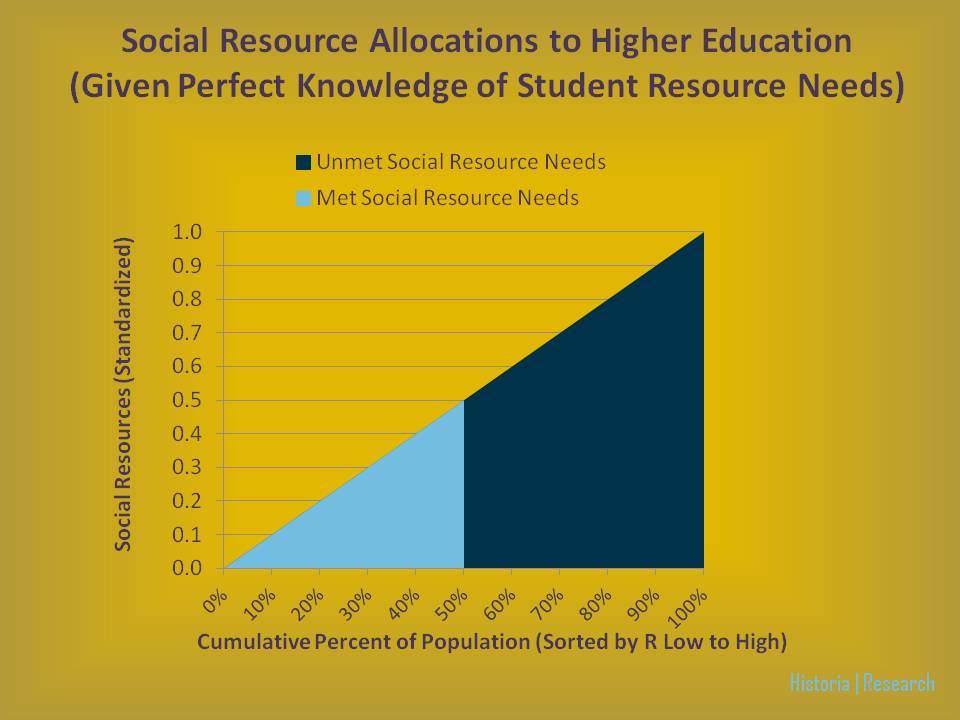

Assume first that the social resource needs (R) of a national population follows a simple linear pattern that can be standardized from 0 to 1.0 (lowest to highest). Assume, also, that this national ecology of higher education has perfect knowledge of the resource needs for each student to succeed such that the population can be sorted from low to high. In Figure 2, the triangular space in light and dark blue represents the total population’s social resource needs to achieve universal student success in higher education, sorted from lowest need to highest need.

Consider, then, a circumstance in which a social state allocates resources sufficient to provide higher education to the “talented” 50% of its population with the lowest needs.

Figure 2 | Social Resource Allocations in Higher Education (Example 1)

As evidenced visually in Figure 2, the unmet social resource needs of the 50% who do not receive higher education (dark blue) far exceeds the met social resource needs of the 50% who receive higher education. In fact, in this simple example, the area representing the social resources provided to the population (light blue) is only 25% of the total social resources necessary (0.5 population * 0.5 standardized social resource needs = .25). In other words, whether due to actual scarcity of social resources for higher education or the lack of political will for student success in the social state, this national ecology of higher education provides only 25% of the social resources necessary to provide equitable outcomes for all students.

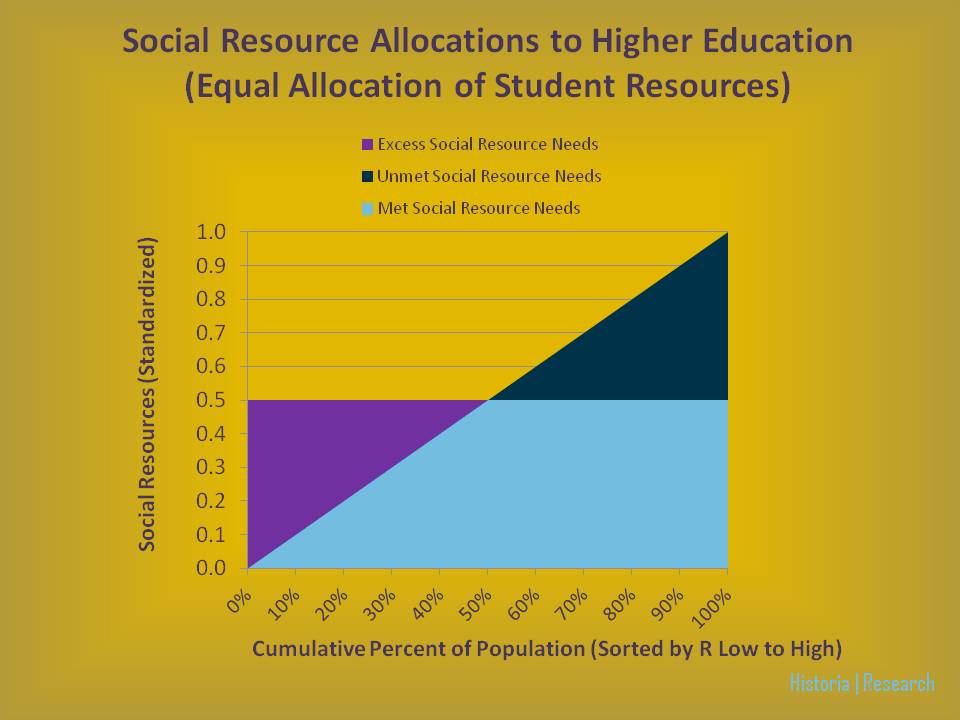

As a second example, again assume the resource needs of a population follows a simple linear pattern that can be standardized from 0 to 1.0 (lowest to highest). In this example, assume also that the national ecology of higher education has the total resource necessary for the success of every student in the population (the complete triangle in Figure 2). This ecology of higher education, however, has no knowledge of the social resource needs of each individual student and chooses to offer every student exactly the same amount of social resources (standardized R = 0.5).

As illustrated in Figure 3, every student now receives a share of the social resources in the ecology of higher education, but again only fifty percent of the population receives the social resources necessary for success (light blue). The other fifty percent receives social resources (light blue), but at a deficit of the social resources necessary for their individual student success (dark blue). In addition, the “talented” fifty percent with sufficient social resources (light blue) also receives a surplus of social resources (purple).

Figure 3 | Social Resource Allocations in Higher Education (Example 2)

In this example, once again, only the fifty percent of the population with the lowest social resource needs receives sufficient allocations for student success. Although the fifty percent of the population with the highest social resource needs receives a portion of necessary allocations for student success (light blue), the deficit (dark blue) and the excess (purple) social resources represent inequitable allocations in an ecology of higher education. In fact, the inequitable allocations in sum (absolute values) equal the insufficient allocations received by the neediest fifty percent of the population. Thus, despite this national ecology of higher education allocating social resource to 100% of its population (light blue), the inequitable allocations diminishes student success for half the population and rewards half of its population with social resources in excess of what is necessary for student success.

In both examples, fifty percent of the population realizes student success (Aq = 0.5), while only one quarter of the social resources are allocated equitably. In the first example, insufficient social resources limited the equity of the ecology. In the second example, inefficient redistribution of social resources from the neediest to the least needy diminished equity in the ecology of higher education. In short, the two simple charts illustrate how insufficient and inefficient social resource allocations account for the failure of an ecology of higher education to deliver on the promise of universal student success. These examples are likely best case examples, as well, since both social resource needs and the allocation of resources to “talented” students may be more like exponential functions that grossly augment the inequity in an ecology of higher education.[2]

Our two baseline examples treat each deficiency separately, whereas all national ecologies of higher education (per Figure 1 above) suffer from both an insufficiency and an inefficiency of social resource allocations according to our formula for student success. Two different ecologies of higher education may produce the same outcome for entirely different reasons (insufficient resources or inefficient allocations), but remain at base commensurate with the other. Without having to know the exact amount of social resources available, the accountability quotient (Aq) for one ecology of higher education may be compared to others ecologies of higher education without regard for the total social resources available for student success and the extent of inefficient allocations of social resources for student success.

The examples therefore suggest a general definition of accountability for every ecology of higher education: Accountability in an ecology of higher education measures the allocation of social resources to maximize student success.

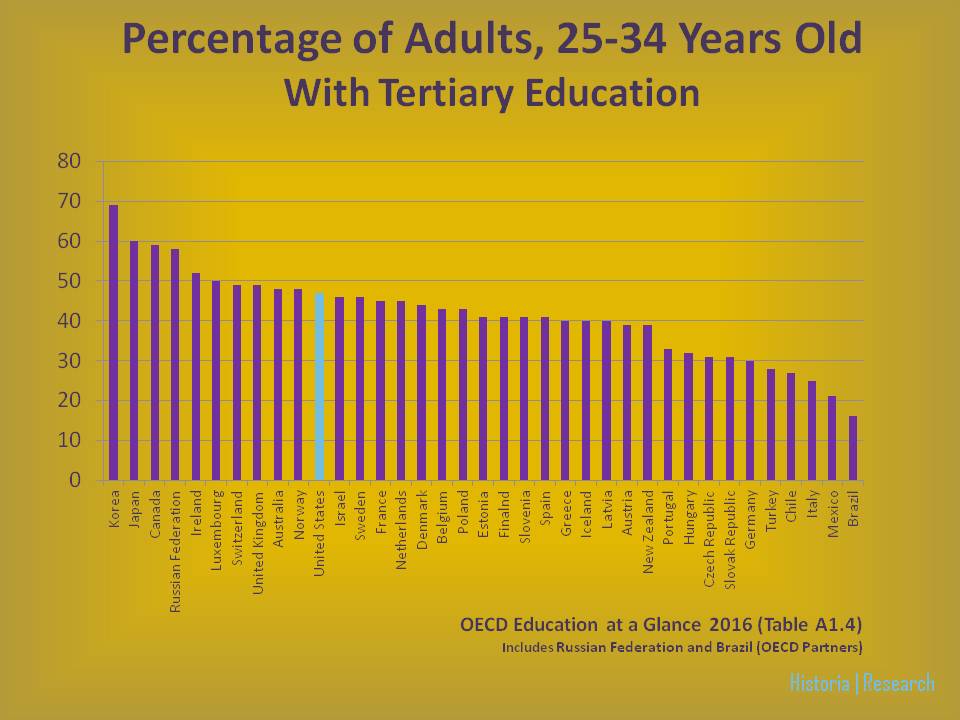

Returning, now, to President Obama’s College Completion Goal and the OECD countries college completion rates for 25 to 34 year old citizens, we find that most national ecologies of higher education have been able to avoid accountability to their national citizenry to a substantial degree while contributing considerable inequity to their (mostly) democratic social states. Using the most current data from the OECD in Education at a Glance 2016, Figure 4 charts college completion rates for 25 to 34 year olds (the accountability quotient) for the OECD countries and other nations cited by the Obama administration in its college completion goal 6 years ago.

Figure 4 | Percentage of Adults Age 25-34 with Tertiary Education (OECD)

As evidenced above, the United States has made modest progress toward President Obama’s 2020 goal. With a tertiary degree completion rate of 47% (Aq = .47), the current cohort of 25-34 year old Americans have improved on the degree completion rates of the 2010 cohort. Nonetheless, well into the 21st century, the majority of Americans, in one form or another, profoundly subsidize the intellectual pursuits and financial gains of of a minority of Americans who benefit from the national ecology of higher education. To meet Obama’s goal within the next four years, tertiary degree completion rates will have to spike by 10 percentage points or more for the generation of Americans born between 1986 and 1995.

In addition, although the U.S. has improved accountability in higher education modestly, other nations have also become more accountable to their populations and the relative position of the United States slipped in the past six years. Currently, in comparison to six years ago, more nations now maximize student success better than the United States. South Korea continues to raise the bar for accountability in an ecology of higher education, approaching a 70% tertiary degree completion rate among its 25-34 year old citizens. Japan, Canada, and the Russian Federation approach the 60% goal set by Obama for the United States. Lastly, per the OECD, Australia, United Kingdom, and Switzerland enhanced student success and degree attainment of its young adults more rapidly than the United States during the past six years.

We conclude then with the observation that, while socio-historical conditions in nation-states typically have worked to limit higher education to a minority of the global citizenry, the trends indicate favor for greater student success and equity in the global ecology of higher education. The Obama College Completion Goal may have seemed like a uniquely American aspiration to faculty and staff at U.S. colleges and universities who feel taxed by the burden of student success, but the college completion trends in the OECD countries and partners signify that accountability efforts in American higher education coincide with a larger, transnational agenda in the world’s democratic societies. A medieval institution in origin that serviced the wealthy and the nobility, the true challenge for the world’s colleges and universities may be to uphold the three missions of higher education while adapting to the forms of inequality that enhance individual freedom and social justice in democratic social states.

A New Vision for Institutional Effectiveness

Accountability measures in higher education speak directly to the equity in college student outcomes for a nation. Although President Obama’s goal for 2020 is ambitious, other nations have already surpassed the goal or made better progress to the goal than the United States. The U.S. ecology of higher education seems to suffer from a lack of accountability and equity that other nations overcome more readily. As a new report from the National Academy of Arts & Sciences states, “The United States’ impressive, if still incomplete, efforts to expand access to college have not been matched by comparable progress in achieving college success.”

Unfortunately, institutions of higher education in the United States remain subject to advocates for the elaborate profusion or federated network (“matrix”) model of decentralized, unaccountable institutional research functions. The old and new visions for institutional research underwrite a flawed system of accountability in which most institutions fail to define concrete responsibilities for student success.

The formulas put forward in Part VII of our series of essays suggest that the link between student success and the accountability of higher education is institutional effectiveness and research. In our paradigm for ecologies of higher education, the efficient and effective allocation of social resources at institutions stands as the single most important contributor to student success. Accountability, therefore, begins with the recognition that institutional research is (1) a social scientific enterprise (2) centralized under a rigorous research program and office (3) in order to contribute scholarship on social resource allocations (4) that advance student success in the global ecology of higher education.

To paraphrase our tagline, the probability for continuous improvement toward equitable outcomes in the global ecology of higher education will increase given more systematic inquiry at the institutions accountable for student success in democratic nation-states.

End of Honors of Inequality

- A presentation of the 2020 College Completion Agenda by the U.S. Department of Education can be found here. The OECD statistics for national college attainment by 25 to 34 year olds may be obtained here. Both sites accessed as recently as August 25, 2016.↵

- An ecology of higher education may redistribute large amounts of its social resources from the neediest students to the least needy students in order to meet the demands for more research (extension) or more training (dissemination) to satisfy the priorities for the three missions of higher education in the social state. In addition, while there is a limit to the social resources that may be redistributed from the least “talented” students to the most “talented” students, there is no limit to the excess social resources the most “talented” students may receive in an effort to advance the missions of research (knowledge extension) and workforce training (knowledge dissemination). For example, institutions of higher education may offer full scholarships to expensive honors programs to “talented” students who do not need such lavish resources to succeed. At the same time, “needy” students will be charged tuition far in excess of the instructional expenditures they receive in order to cover the costs of educating the “talented” students. Nonetheless, the linear representation of social resource needs provides a baseline for analysis.↵